After Identity: Mentalities, European Asymmetries and the Digital Turn

A digital view of Europe

As we saw, both the idea of a collective mentality as an imagined community – a sort of Anderson 2.0 – and the process of asymmetrical cultural referencing that influences a mentality, are based on repetition. Mentalities emerge through repetitive broadcasting. This brings me to the use of computers in historical research. The sometimes bombastic language used by ‘big data’ enthusiasts may not be entirely convincing, but no practitioner of the humanities will deny that we live in a digital age and that this world will not be going away any time soon. Actual practice is of course more complicated than pretentious expectations. On the one hand we need to beware of reducing reality to the handling of data by a mere algorithm. Computers are capable of modelling data in extremely sophisticated ways, but at this point in time they cannot in any sense be a replacement for people. On the other hand we cannot help but note that ‘big data’ is hardly a novelty. Historians have been seeking for patterns in the past since Herodotus, so the call to engage with them is not particularly revolutionary. At the very least, computer-assisted research can serve to look anew for larger patterns (such as mentalities) in larger amounts of data (such as newspaper articles).13

I have argued above that mentalities arise from the iteration in public discourse of ideas, points of view, arguments, conceptions, opinions, beliefs, and so on and so forth, that occur and reoccur as part of the dominant data flows in society. For most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, newspapers comprised a very significant, if not the dominant, data flow in society, thereby influencing mentalities on a national level. In other words, digitized newspapers likely allow us to examine the content and development of those mentalities. In the final instance a computer is not much more than a glorified counting machine, and the one thing a computer is able to cope with is repetition. It would be logical, therefore, to exploit such frequency generators to map mentalities.

I will offer a simple example of the way computers allow us to chart mentalities, based on the periodicity of newspapers. The example concerns a particular conception of Europe as an aspect of the Dutch national mentality: the idea of rivalry as a common European bond. The historical foundation of European power has frequently been attributed to the fact that since at least the medieval period but more obviously since the sixteenth century, the European continent has functioned as a complex of mutually competitive territories. The idea that not just Europe’s rise to global economic and military dominance but its very unity and coherence are to be found in the fact that it is so fragmented may sound a little bizarre, yet it has always been a serious point of view for both intellectuals and politicians wrestling with Europe’s ‘identity’.14 The cycle of war and peace between Habsburg and Hitler, the economic struggles in Europe’s history from the Dutch East India Company to the scramble for Africa, and the cultural variety among the European nation states has often been summarized in the dictum, ‘unity in diversity’. The dictum was even chosen as the official rallying cry of the European Union in 2000, with the intention, obviously, of stressing union over disunion. Be that as it may, we need not look far for a thin description of Europe: the official website of the European Union offers a version of the motto ‘united in diversity’ in no less than twenty-four languages, ranging from the Dutch in verscheidenheid verenigd to the German in Vielfalt geeint.

Almost two decades later the motto sounds a little like an admission of weakness. It is doubtful, one suspects, whether diversity can function as the basis of a strong polity. But that is not the point. The metaphor of Europe as a family of troublesome and often dysfunctional relatives has frequently appealed to the European imagination. And despite the cynicism it may prompt, there is something to the motto. Friendly competitiveness as a modern, sublimated version of traditional violence was strongly encouraged in the twentieth century, when the various nations got together under European colours in a joint effort to win palms of honour. Some of the earliest examples stem from the period between the two World Wars. In the Interbellum, for example, a rather innocuous and once popular competition between the most beautiful women of Europe began to be organized: the Miss Europe pageant. Newspapers had a field day. The public loved stories about European girls who, thanks to their election as Miss Europe, were actually invited to America, the high point of all pageants. The press lapped up the scandals about winners who ended penniless and friendless and ultimately committed suicide.15

The Miss Europe elections were resumed after the Second World War, when they often took place in the former European colonies. In 1952 even Turkey was allowed to supply the loveliest Miss of all. In this respect the Miss Europe Competition resembles the Eurovision Song Contest, which today includes not just Turkey, but also Russia and even Australia. Political and cultural definitions of Europe overlap but they do not coincide: it seems that competitive European culture was more inclusive than the regulated market of coal and steel. It is the sheer extent of this competitive culture across the western edge of Eurasia that makes it constitutive of a twentieth-century thin description. When and how were European competitions covered in Dutch newspapers? How popular were they? Can we assess the impact on the Dutch mentality of the idea of Europe as a unity based on amicable rivalry?

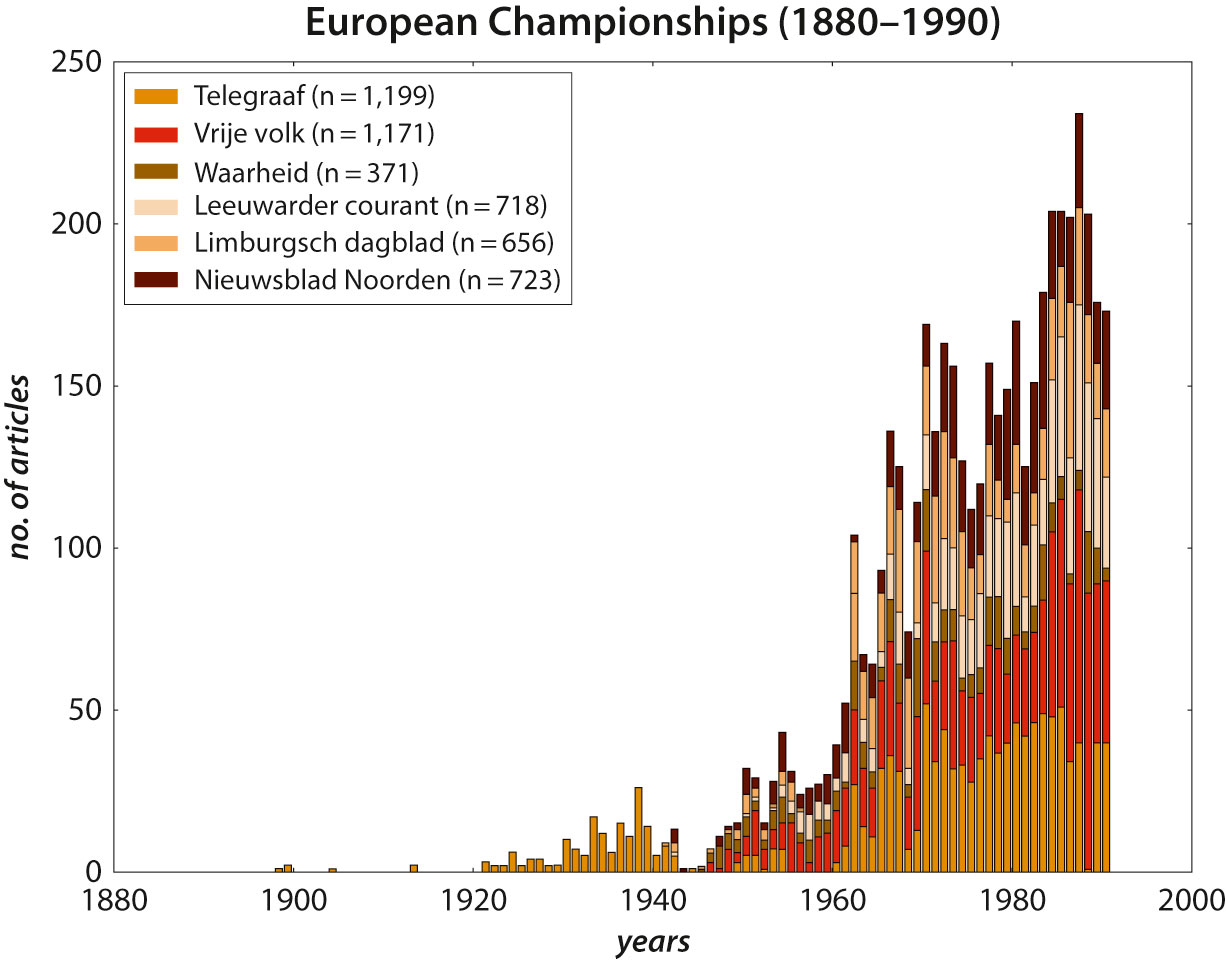

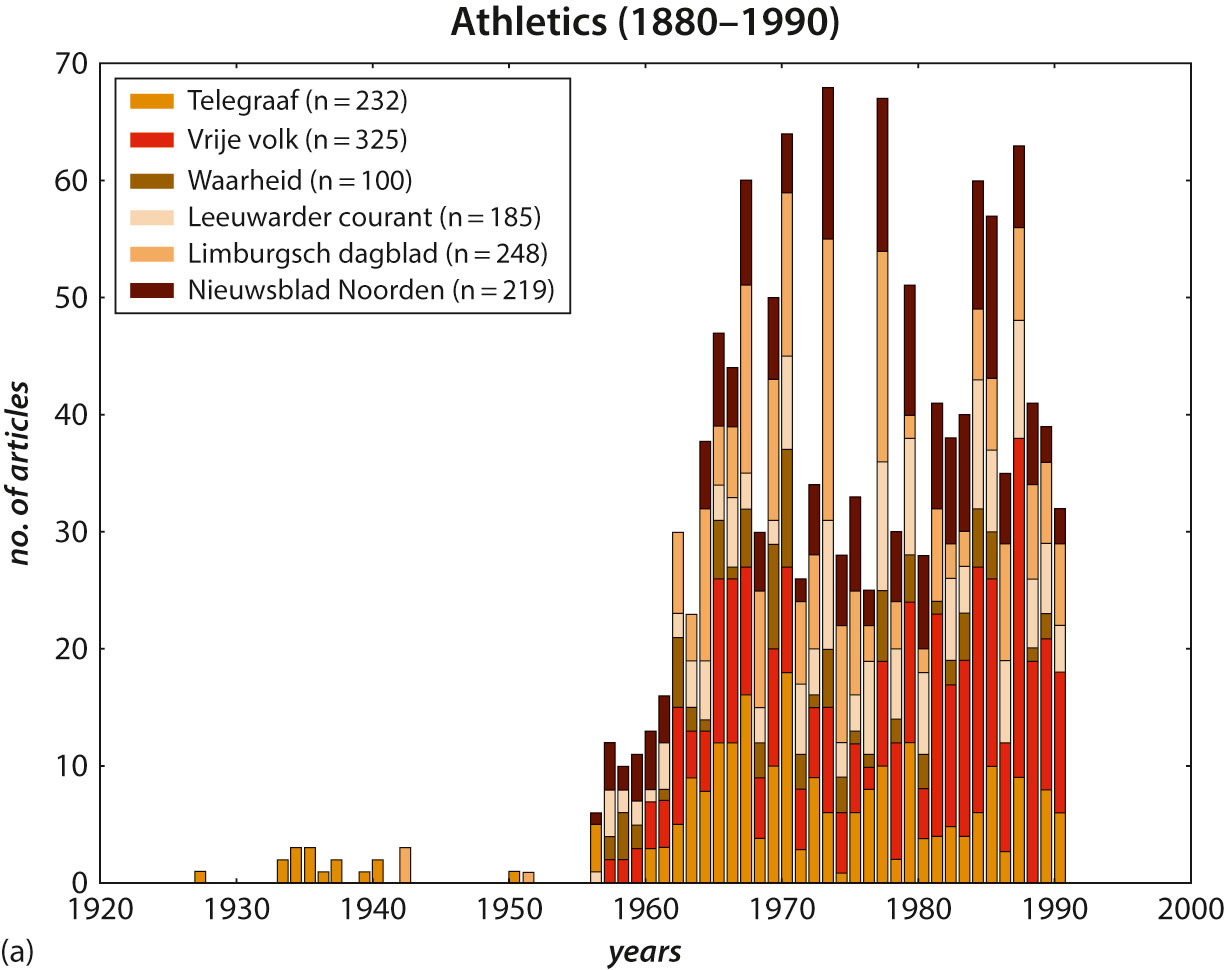

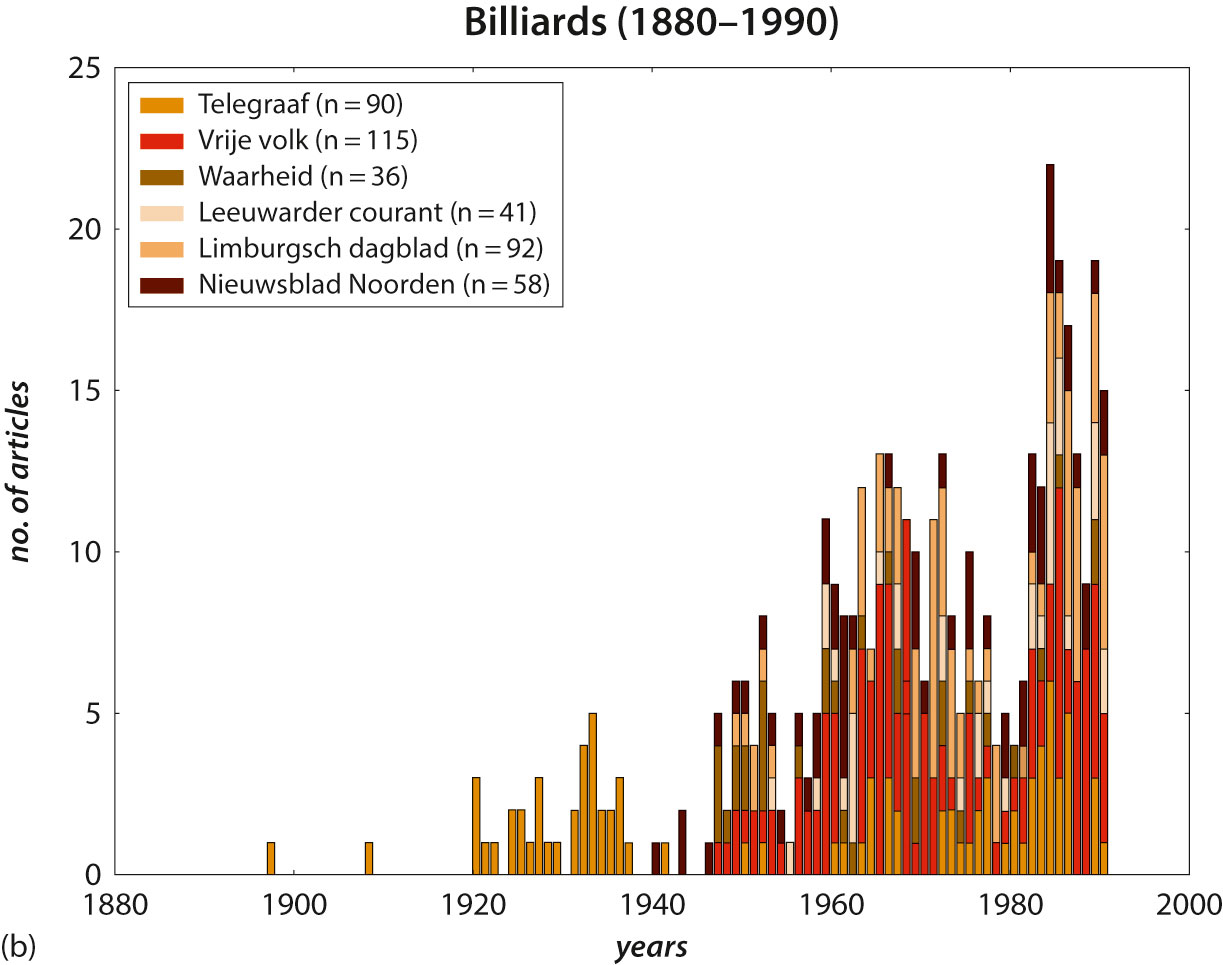

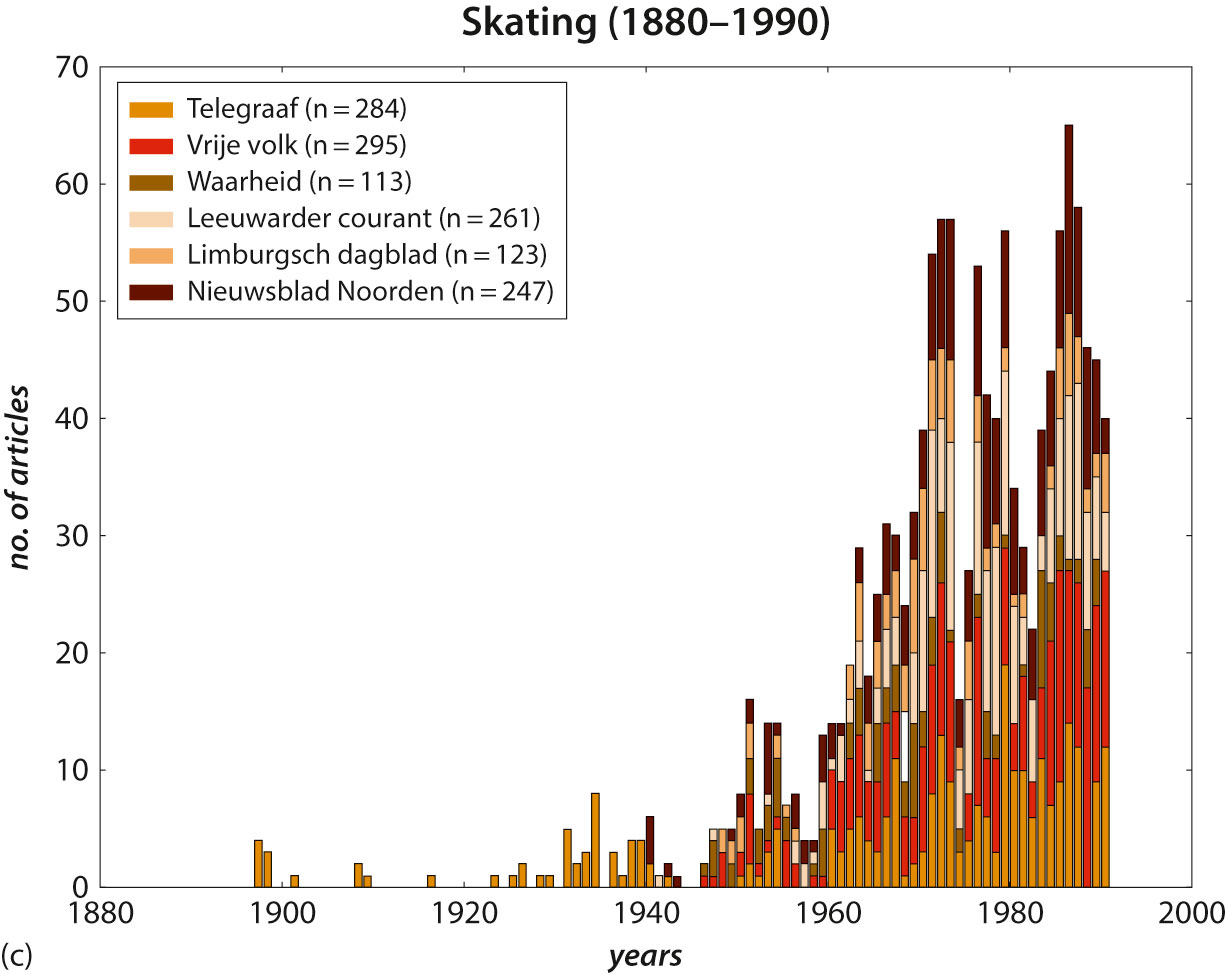

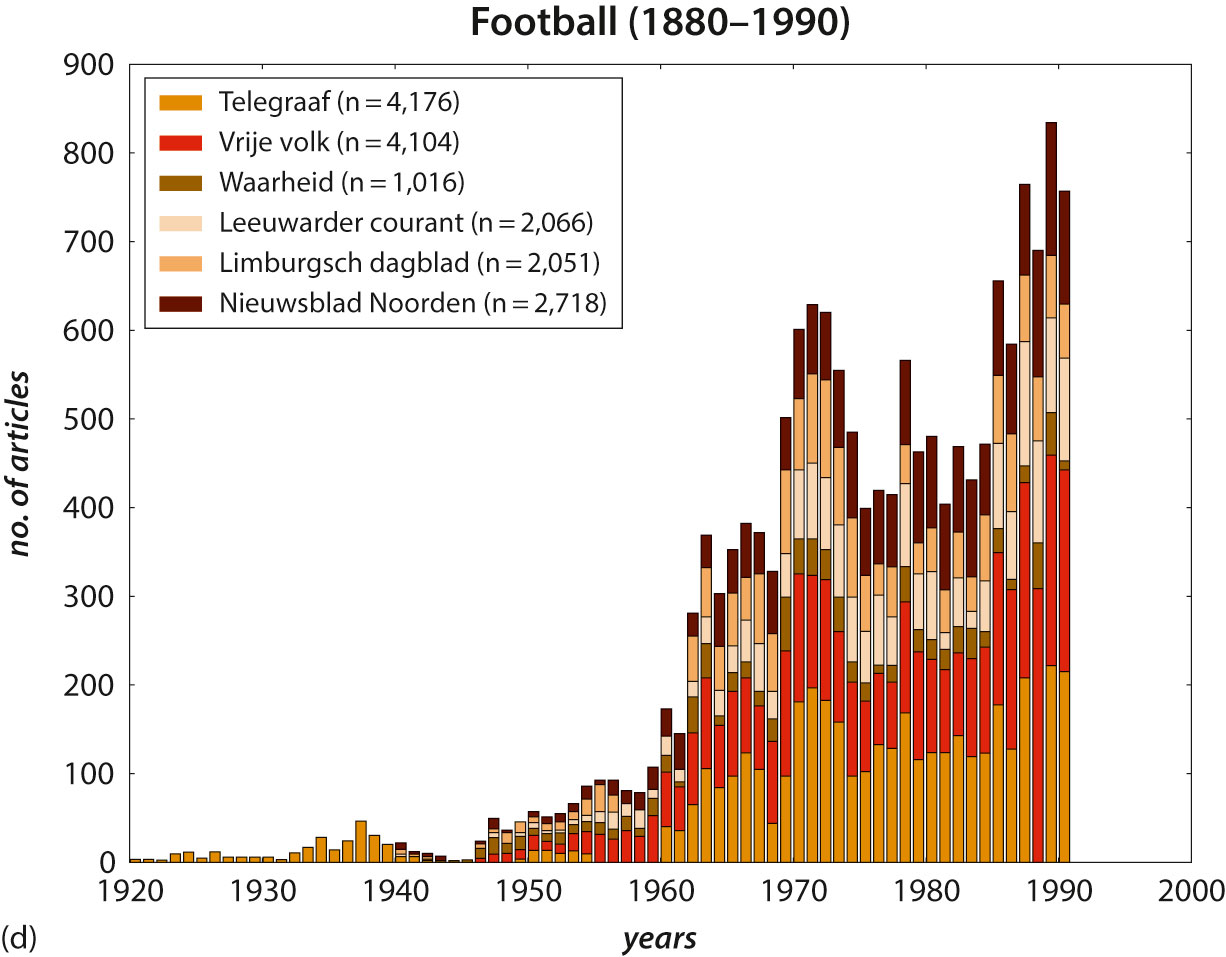

Of the many contests held during the twentieth century, sports competitions stand out in terms of the amount of news coverage they attracted. Newspaper articles frequently mention the word ‘Europe’ in combination with specific sports, and they do so in a very clear pattern. It is evident from Figure 4.1 that sporting activities did not manifest themselves as a peaceful version of the traditional European melee prior to the Second World War. This histogram represents the absolute number of hits for the term ‘European Championships’ over the twentieth century for six Dutch newspapers. Evidently, Europe became recognizable as a sporting continent only after 1950. The same pattern manifests itself for all articles that mention ‘Europe’ in combination with major or minor sports, whether we look at athletics, billiards, skating or football (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.1

Stacked bar chart of absolute occurrences per year for the term ‘Europe(e)s(ch)e kampioenschap(pen)’ in newspaper articles in De Telegraaf, Het Vrije Volk, De Waarheid, Leeuwarder Courant, Limburgsch Dagblad and Nieuwsblad van het Noorden (1898–1990). Made in Python Matplotlib.

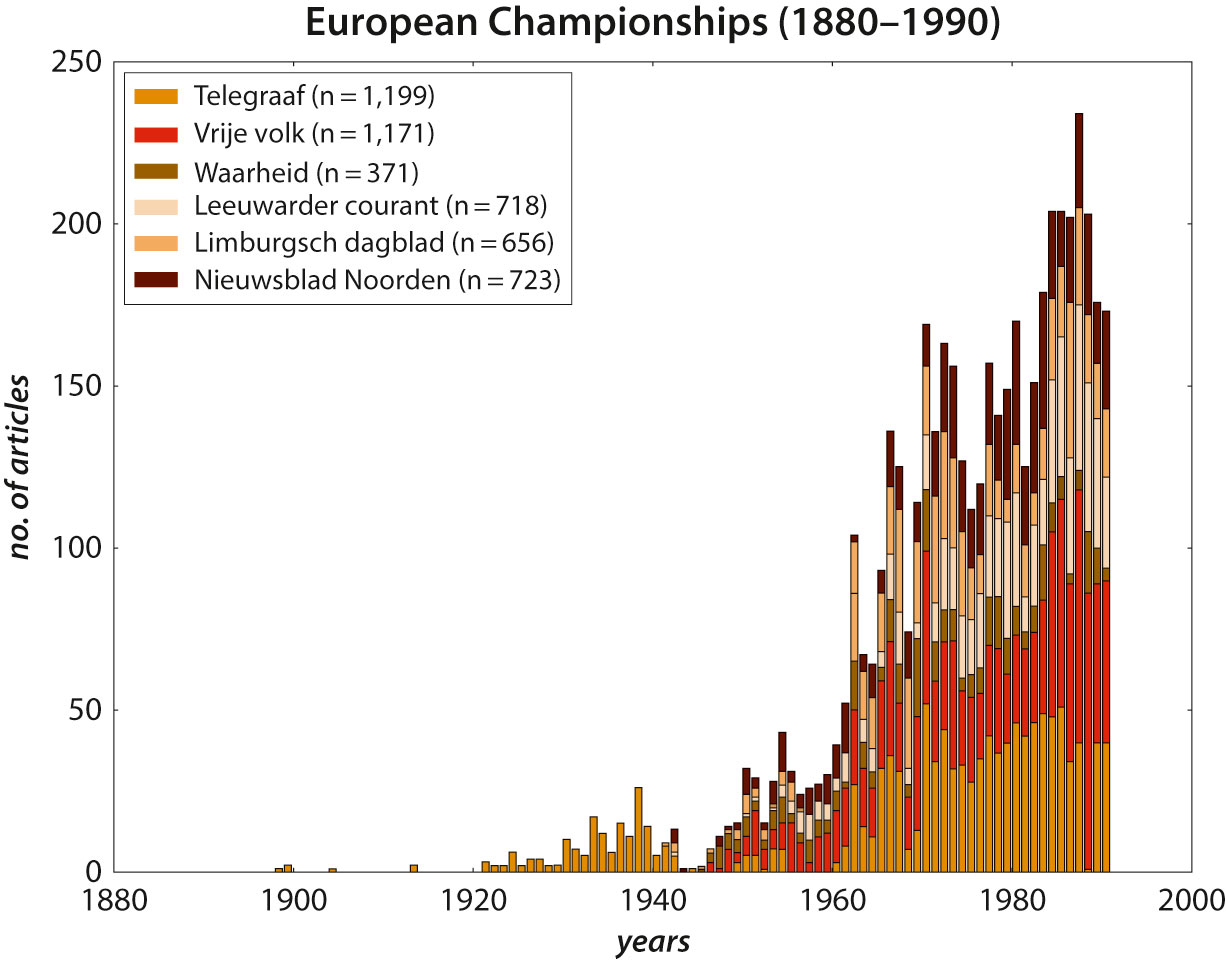

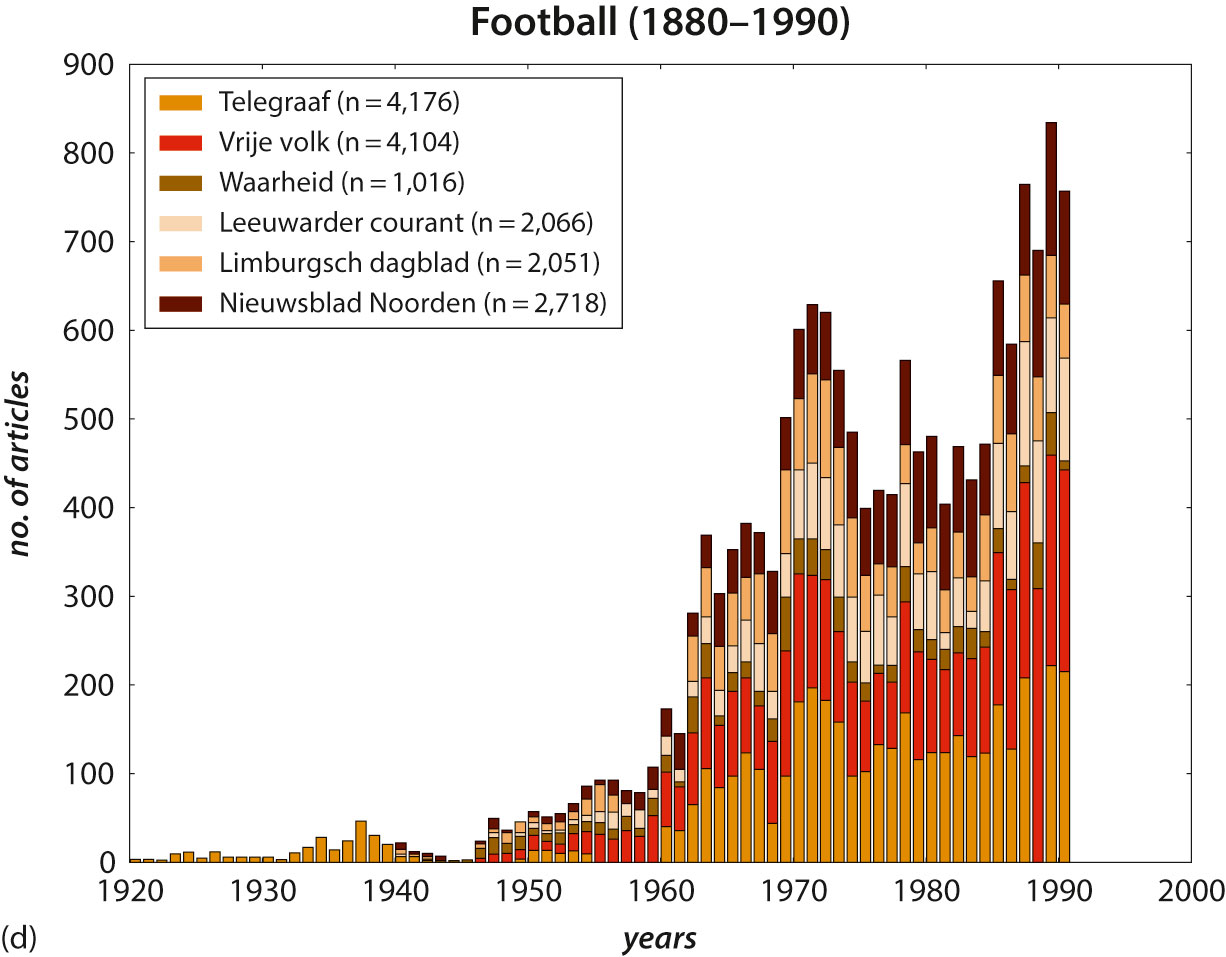

Figure 4.2 (a–d).

Stacked bar charts of absolute occurrences per year for ‘Europa’ in combination with ‘atletiek’, ‘biljart’, ‘schaatsen’ and ‘voetbal’ in newspaper articles in De Telegraaf, Het Vrije Volk, De Waarheid, Leeuwarder Courant, Limburgsch Dagblad and Nieuwsblad van het Noorden (1898–1990). Made in Python Matplotlib.

For Europeans, of course, the prime sporting activity is football, while the key Dutch newspaper is De Telegraaf, a popular tabloid-style daily famous for its sports journalism.16 Interestingly, in light of the European Union’s official motto, newspaper accounts had little to offer in the way of the Europeanness of football competitions. For example, little if nothing was said about a ‘typically European’ football style. In the one single instance (out of some 10 million digitized newspaper pages) that Dutch journalists used the exact phrase ‘typically European’ in relation to football, they quoted a foreigner. The article appeared, rather coincidentally, in De Telegraaf at the very end of what for Dutch football fans would prove to be the most memorable year of the century: 1978, the year in which the Netherlands lost the World Cup to Argentina. In an interview, the Argentinian forward Mario Kempes said:

Dutch football deserves a big compliment. The Dutch play typically European football, but by fits and starts they bring a South American ‘touch’ to their game. That makes them so unpredictable. Football needs to be well organized on your side. Otherwise you’ll never get that far.17

Kempes seems to have meant that playing in a well-organized fashion is typical for European football, but the fact that a South American said so brings us back to the kind of argument made by Samantha Bee in repudiating racism as a non-American habit. It is not certain whether the Dutch recognized the attribution: the Self does not necessarily recognize the things ascribed to it by an Other. Presumably the Dutch felt as little called upon to regard their football style as typically European in 1978 as they are inclined to see racism as part of the European identity today. More important, however, is the fact that the notion of a typically European football style did not resonate among the Dutch themselves.

Clearly, no European frame of reference emerges from the newspapers. The question then arises whether newspapers dealt with post-war competitive Europe in relation to its constitutive nations. We could ask whether (and if so, how) the various European countries mentioned in newspapers functioned as reference cultures for the Dutch. How well did the English, the Italians or the Spanish play football? Were their talents – solid English stamina, defensive Italian catenaccio or even the Spanish penchant for making sneaky fouls – appreciated as something the Dutch should follow? As I have argued, whether or not the presence of such ‘Others’ led to the construction of a ‘Dutch identity’ is not the interesting point. Such contentions tend to lead to never-ending and therefore meaningless discussions about ‘whose identity?’ and ‘which identity?’ The more significant question is whether the mutual bonding of European nations through competitive activities led to a sense of Europeanness in the Dutch collective mentality. Surprisingly, however, newspaper accounts had little to offer in the way of this kind of Europeanness. I have not been able to find any significant iterations over a longer period of time of specific national attributes. Applying the phrase ‘typically Italian’ to football gives us three hits in the complete, ten million-plus data set. One hit refers to a ‘typically Italian dish such as macaroni or spaghetti’ (served while watching a football game on television in 1990); a second mentions ‘the typically Italian exuberance’ of the Italian president, who apparently kissed everyone on board the plane that was flying him back to Rome after Pisa defeated Ascoli in 1988; only the third condemns the ‘typically Italian’, unsportsmanlike style of AC Napoli, whose unwilling and uninspiring defensive play ‘killed’ the match against Ajax Amsterdam in 1970.18

The lack of cultural references either to Europe or its constitutive nations leaves us with the mere mention of those nations. Were some sporting countries mentioned more often than others, so that they were eventually lodged in the minds of Dutch readers through constant repetition? The relative frequency with which nationalities occurred over time in football news offers an image of the geographical rather than cultural formation of Europe as an aspect of the Dutch twentieth-century mentality. To ascertain this, we need to chart European football games and plot the historical variants of twentieth-century nationalities mentioned in newspaper articles. Was the Icelandic football team on the Dutch radar at all? How popular were the English? Did sports journalists connect Europe to Russians or Turks or even Egyptians, as their colleagues did with respect to the Miss Europe Pageant or the Eurovision Song Contest? What did this mean for Europe as a geographical framework in the Dutch collective mentality?

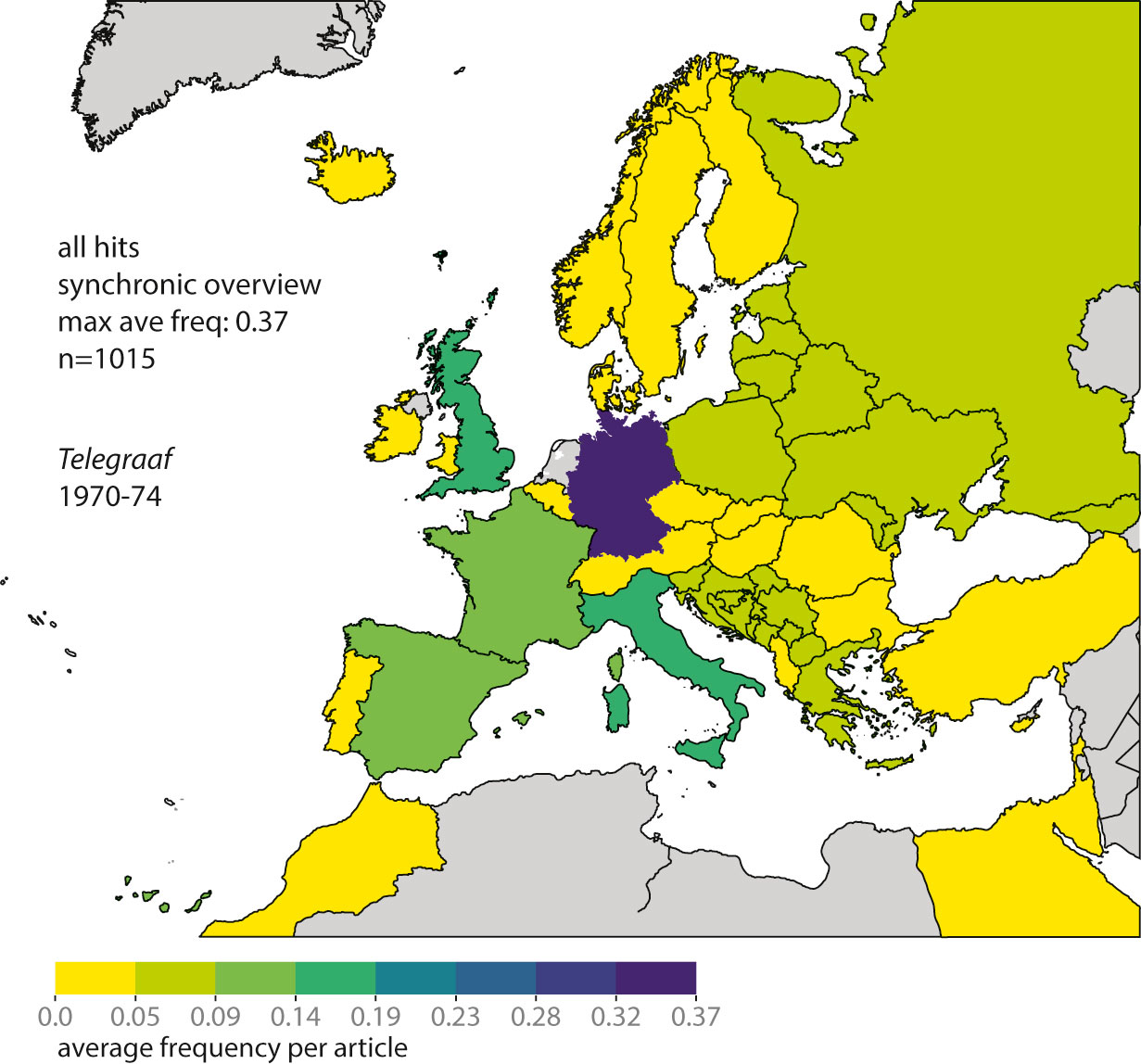

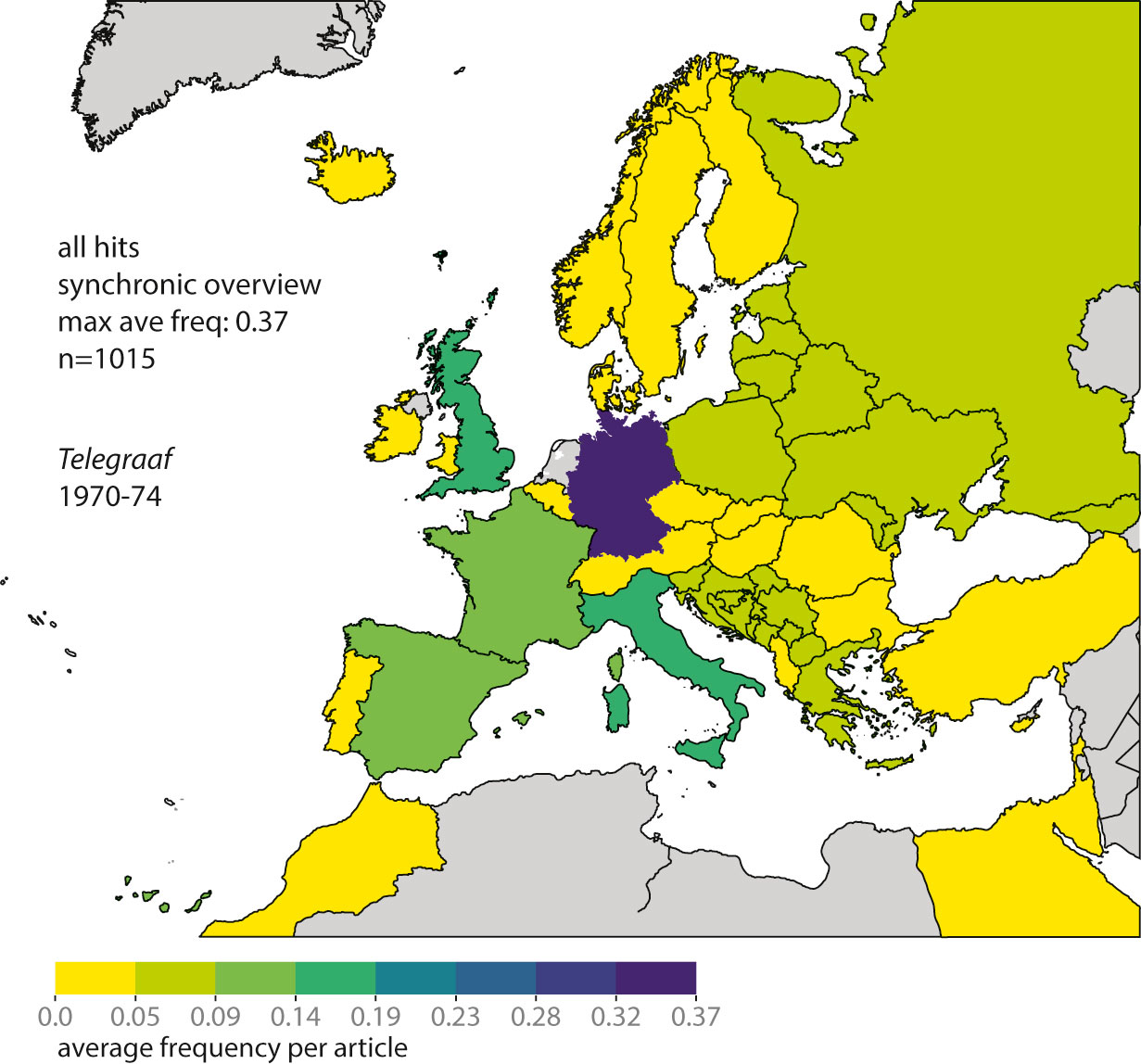

Directly after the First World War De Telegraaf established an image of soccer-playing Europe that would hold its ground until the end of the twentieth century. Despite the inevitable variations in charting European football competitions, one thing is abundantly clear: from the outset a central role was reserved for Germany. Moreover, the image of competitive Europe during the 1920s was no different from the image that emerged during the 1970s. The five years from 1970 to 1974 offer a division of football-playing nationalities that is representative of the whole post-war period (see Figure 4.3). The Germans are way up in the charts. Next come the English and Scots, the Italians, the French and the Spanish. The remainder includes substantial parts of Eastern Europe, even during the Cold War, especially Poles, Russians and Yugoslavs. However, although Eastern Europe and Scandinavia may have been present, from a statistical perspective they were quite irrelevant, as were Iceland and Greece.

Figure 4.3

Nationalities in football: Map of Europe displaying average relative frequency of articles in De Telegraaf (1970–4) mentioning ‘Europe’ in combination with nationalities. Most historical countries like the USSR and Yugoslavia have been reconstructed (although twenty-first-century boundaries show through). Germany has been taken as a whole; the United Kingdom has been broken down into its constituent parts. Frequencies refer to all (rather than unique) hits per article and they are compared across space within the given period (i.e. synchronically rather than diachronically). Made in Python Basemap and Matplotlib.

The result of constant repetition in sports news was an image of Europe represented by a Saint Andrew’s Cross of nationalities that had its pivot somewhere in the neighbourhood of Luxembourg, connecting Real Madrid and the Hamburger Football Association with SSC Napoli and the Glasgow Rangers. This Saint Andrew’s Cross was established in the minds of Dutch readers as a qualitative, geographical frame of reference. As such it was a significant aspect of twentieth-century reality, internalized in a collective mentality over several decades.