9.1. How do poor urbanites source their food? Evidence from African cities

Although there has been a growing interest among policy-makers and planners in the role of urban agriculture in addressing urban food insecurity, improving nutrition and increasing dietary diversity, the evidence base to support the assumption of its central role is weak (Zezza and Tasciotti 2010). Warren and colleagues (2015) argue that this is because of poor-quality study designs rather than because the link has been disproved. These authors find no reason to discourage the practice of urban agriculture but suggest that its potential to address food insecurity should be more thoroughly tested before it is adopted and resourced as the primary policy tool to address urban food insecurity. Research specifically in the African context found that the prevalence of urban agriculture varies greatly between cities owing to distinctive local histories and geographies and was unable to generalise about the potential of urban agriculture to address food insecurity (Frayne et al. 2014).

Despite the overwhelming policy and planning focus on urban agriculture, the vast majority of African urban residents obtain most of their food from various types of retail outlets (Maxwell 1998; Crush and Frayne 2011b). The structure of this market is changing rapidly as supermarkets expand into urban Africa and diffuse their products from wealthy to food-insecure households (Weatherspoon and Reardon 2003). Research in Southern African countries has shown particularly rapid supermarket growth driven in part by large South-African-based food retail chains that have invested heavily in larger and secondary cities (Crush and Frayne 2011b). By way of example, Acquah and colleagues (2014) show how Southern Africa’s ‘supermarket revolution’ has transformed the way in which urban (and rural) residents of Botswana source their food. Supermarkets now handle around 50–60 per cent of food retail in cities and major urban villages in Botswana. The AFSUN survey of residents of a low-income area in Gaborone found that 92 per cent of households reported using supermarkets as a source of food. Only four per cent of households never shopped at supermarkets.

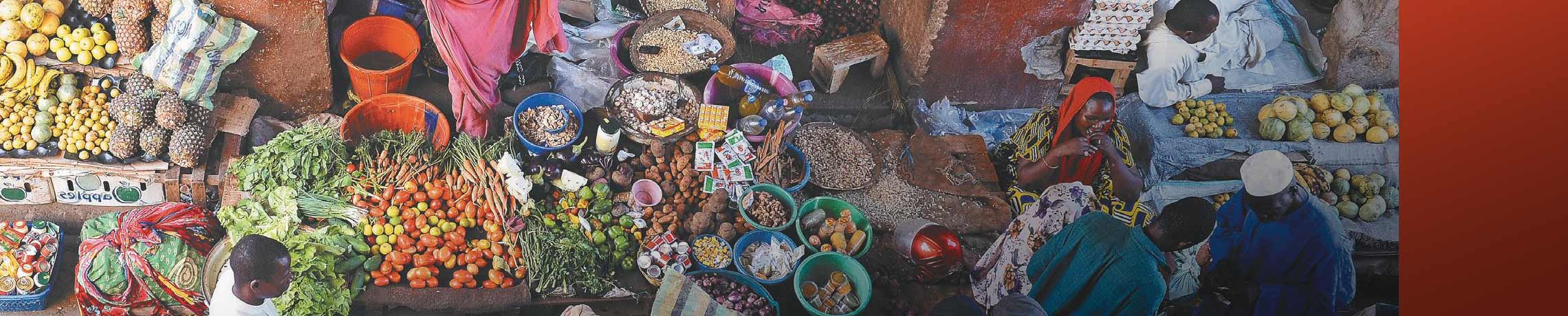

However, the expansion of supermarkets does not imply a declining importance of informal food retailers in supporting urban food security (Battersby and Watson 2018), as research in Lusaka (Zambia) has shown (Abrahams 2010). In this city informal food networks and outlets still play a very important role and integrate in various ways with the formal food sector. Lusaka is unusual in some respects, however, in terms of the role played by the municipality in supporting the informal food sector (see below). Although Lusaka may have unique characteristics, Reardon and colleagues (2007) have identified a process of ‘consumer segment differentiation’ whereby consumers buy different types of products at different types of market.

In most cities in Southern Africa the growth of supermarkets has had an impact on informal food suppliers, and evidence from Botswana (Acquah et al. 2014) suggests that the size and growth of the informal economy have been constrained by supermarket growth. However, informal food retailers (whether pavement trade or in markets) have advantages in serving low-income households, since they can gain better physical access to them, have lower overheads, can break bulk and sell in small units and sometimes offer credit (Battersby 2012). The larger formal supermarkets tend to locate closer to middle-class areas and are often only accessible by car, but are frequently able to sell cheaper than informal traders, since they can access in bulk and have control over supply chains. Formal and informal retailers also link in a variety of ways (informal sellers sometimes using larger formal outlets as wholesalers) and consequently the way the systems pattern spatially in any city, as well as the extent to which informal traders are being undermined by supermarkets, depends very much on context (Crush and Frayne 2011a). It is for this reason that the concept of the ‘food desert’, often used in Global North literature to describe urban districts where food is difficult to access, was found to have less relevance in the AFSUN research sites: small and informal food traders are highly flexible and mobile and are able to occupy the spaces that have no supermarkets (Battersby and Crush 2014).

As patterns of urban food retail transform in Africa it is important to consider what changes are happening in the resultant food system. Research in Cape Town found that the largest four supermarket companies (which account for 97 per cent of sales in the formal food retail sector) estimated that, although 56 per cent of their vegetables came from within 200 km of the city, just five per cent of grain did, and, even though there is considerable meat and poultry production in the region, only a third of protein came from local areas (Battersby et al. 2014, 159).

Similarly, informal traders cannot be assumed to be sourcing locally. A survey of 100 informal traders in Cape Town found that they bought food for trade from sources that have local, national and international supply chains. Over half of traders bought from wholesalers (largely for processed foods and meat), who source processed foods from national and international producers. The main source of fresh produce was the Cape Town Fresh Produce Market, which procures locally where possible, but also sells key products that cannot be produced locally (such as bananas). Some traders also buy direct from farms, but this is not often possible given existing contracting agreements between farmers and retailers (Battersby et al. 2014, 163).

Similar experiences of non-local food supply chains are to be found throughout Africa. In Maputo, Mozambique, the frozen chickens sold by street traders are Brazilian (Raimundo et al. 2014, 27). In Kitwe, Zambia, fish sold by traders come from local sources and also from Namibia and China (Siyanga 2016). In Kisumu, Kenya, eggs being sold by wholesale traders in Kibuye market were from Uganda (Hayombe et al. 2018). Throughout West Africa, imports now supply more than 40 per cent of the demand for cereals (Moseley et al. 2010, 5774). It is therefore essential that food security policies consider the governance of formal and informal, and local and global components of, urban food systems.

Given the importance of context in shaping the distribution of food outlets and the links between this and urban food security, the next section focuses on a case study of Cape Town, South Africa.