Fonthill Abbey

The best-documented, best-researched and most frequently told story of the Fonthill estate is the rise and fall of Fonthill Abbey. William Beckford’s extraordinary creation captured people’s imagination from the moment it was begun in 1796, and has continued to fascinate and inspire ever since, a fascination greatly enhanced due to the collapse of the building in 1825 and its subsequent demolition. Understanding of Fonthill Abbey exists through images, written accounts and a single remaining fragment that stands as an echo of the building that defined the romanticism of the Gothic Revival.

The seeds of Fonthill Abbey were sown in 1790 when Beckford wrote a letter to Lady Craven, in which he made what would become one of his most frequently quoted statements:

One of my new estates in Jamaica brought me home seven thousand pounds last year more than usual. So I am growing rich, and mean to build towers, and sing hymns to the power of heaven from their summits.99

This combination of architectural fantasy and financial reality underpins the evolution of Fonthill Abbey; if the building was defined by Beckford’s imagination, it was also dictated by the fluctuations in the income from his estates in England and, more vitally, Jamaica (see Chapter 13).

The beginnings of what would become Fonthill Abbey can be traced to the period when James Wyatt was first commissioned by Beckford to work at the estate in the early 1790s. As early as 1792 the architect was drawing up designs for a tower.100 Two years later, while abroad in Portugal, Beckford wrote to Wyatt informing the architect that his passion for St Anthony of Padua could be temporarily assuaged by his creating a sanctuary at his residence in Lisbon. This would be enough to tide him over, until he could carry Wyatt’s ‘magnificent plan for the chapel upon Stop Beacon into execution’.101 Beckford’s periods of residence in Portugal between 1793 and 1798 provided him the opportunity to visit the monasteries of Alcobaça and Batalha, possibly at the suggestion of Wyatt; those visits contributed to his ideas for Fonthill, as did his earlier visit as a young man to the Grand Chartreuse in Switzerland (see Chapter 11).102

By the summer of 1796, the site for the tower had moved from Stop Beacon further east; by November Beckford’s ‘Abbey in the Woods’ had reached 200 feet in length with ‘a good part of the building’ having already reached the first floor.103 By 1797 it was still a ‘little pleasure building in the shape of an abbey’, not finished but already filled with painted glass, a gallery, the long-imagined chapel to St Anthony of Padua and a tower 145 feet high.104 The building would have been a striking scene to come upon when riding through the landscape from Fonthill House, functioning as both a feature within the landscape and a retreat for its creator.

Wyatt exhibited a view of Fonthill Abbey for the first time at the Royal Academy in 1797, and would do so again in 1798 and 1799. His surviving sketches (Figures 4.15 and 4.16) illustrate the changing ideas for the building, starting with the earliest scheme for a tower inspired by the mausoleum of King John at Batalha in Portugal.105 This was the building as first encountered by J. M. W. Turner and recorded by him from the south-west.106 Several ideas by Wyatt were clearly being developed during 1797–9, and two later sketches show the existing elements of the building, the south range, fountain court and cloister, main hall and tower base as constructed, joined by proposals for the northern range and an increasingly elaborate tower. Ian Warrell’s unpicking of the series of views of Fonthill by Turner further illuminates the process of construction and collapse that Fonthill Abbey experienced during these early years.107

Fig. 4.15

James Wyatt, Preliminary Design for a Residence for William Beckford (design for Fonthill Abbey as seen from the south).

SA55/5/1, 98518, RIBA Collections.

Fig. 4.16

James Wyatt, design for Fonthill Abbey.

SA55/5/2, 98519, RIBA Collections.

An initial collapse of the Abbey tower while under construction in May 1800 was recorded by Beckford:

So, after a Somersault very neatly performed in the higher Regions of the Air, down came boards, Beams and Scaffold poles: but so compactly and genteelly as not to have shaken a single Stone of the main Edifice or injured the smallest ornament.

The main body of the building survived relatively intact, so plans for the new tower were immediately begun, Beckford exclaiming ‘We shall rise again more gloriously than ever’.108 Press notices of the fall would only have encouraged Beckford to continue work, knowing that the news-hungry public would be awaiting further information about either the failure or triumph of the Abbey.

In December 1800 Beckford invited his second cousin, Sir William Hamilton, accompanied by his wife Emma and her lover Horatio Nelson, to visit Fonthill. The very public arrangement of this trio would ensure that news of the visit would once again reach the press. Beckford embraced the opportunity which the Christmas party presented for being seen in the company of England’s hero of the Battle of the Nile. The Hamilton–Nelson visit was the only major entertainment that the Abbey would ever host, and the published account captures the building not long after the initial tower’s collapse, offering an insight into the interiors of the building at the point when Beckford must have been considering whether or not to relocate his household there.

An account of the party was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine in April 1801, most probably written by Henry Tresham, who had been present as a guest alongside Wyatt and the artist Benjamin West. He describes the journey between Fonthill House and the Abbey as a procession expertly choreographed by Beckford. Lamps in the trees illuminated the route and drums and music sounded through the woods. The Abbey was also illuminated, rising up out of the shadows of the surrounding trees. In staging the journey to the Abbey this way Beckford captured the change his guests would experience in moving from the politeness and formality of his father’s house to the romance of his own creation, a physical retreat into an apparent other realm. After an elaborate banquet designed to echo a medieval feast the guests were then shown the ‘finished apartments’. They passed up a staircase flanked by people costumed as living statues in hooded gowns, through a salon filled with Beckford’s collection and into the library where, passing through a ‘large Gothic screen’, they entered the main destination: the first floor gallery. The gallery, eventually known as the St Michael’s Gallery (Figure 4.17), was already fully fitted up with Beckford’s statue of St Anthony by Rossi standing at its northern end.109

Fig. 4.17

Fonthill Abbey, South End of St Michael’s Gallery.

John Britton, Graphic and Literary Illustrations of Fonthill Abbey, 1823, plate 9, Beckford’s Tower and Museum.

The guests on this night were the privileged few who were allowed access to Beckford’s sanctum. John Britton lamented not long after that he was not allowed access to the Abbey, ‘Mr Beckford having judiciously determined to keep it secret from the public eye till entirely completed’. The reader is further teased by Britton concluding ‘when finished, it is intended to be opened for public inspection’.110 In this one statement Britton both encouraged the curiosity of his readers about both Fonthill and Beckford, and arrived at the perfect way to end a published account: whetting the appetite for more information about the building. Britton would himself eventually provide such information in a full-length study of Fonthill Abbey published in 1823.

Beckford moved from Fonthill House to the Abbey in 1801 and took up residence in the rooms in the southern wing. He lived quietly, but occasionally entertained visitors who would appreciate what he was trying to conjure-up out of the woods. One such visitor was the artist Benjamin West, who on encountering the Abbey thought it ‘a place raised by majick, or inspiration, [rather] than the labours of the human hand’.111 Progress at the Abbey was slow between 1802 and 1805, due both to lack of funds and to Beckford’s absence in France. When Lady Ann Hamilton visited with Beckford’s daughters in 1803 plans were in place for the next major addition to the building, the north wing, and her account of this visit provides a glimpse into the interiors which Britton had been prevented from seeing. Her route through the building matched that taken by Sir William Hamilton and Nelson three years earlier, and again ended in the gallery, by then 136 feet long but still terminating at the space below the Tower. She records the interiors and sketches examples of furniture, noting the extensive use of both natural light and candelabra, and was particularly struck by the painted glass windows showing the monarchy in the dining (or Abbot’s) parlour in the south range and above in the gallery.112

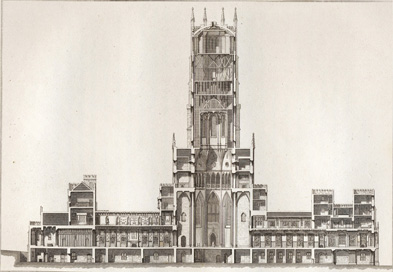

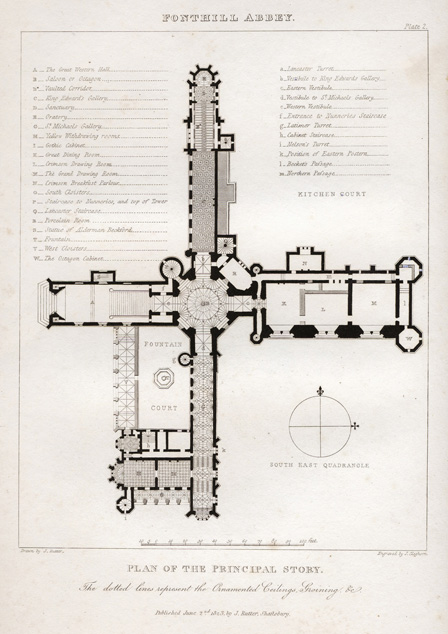

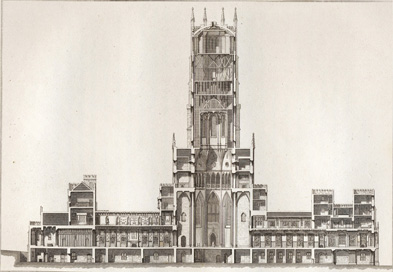

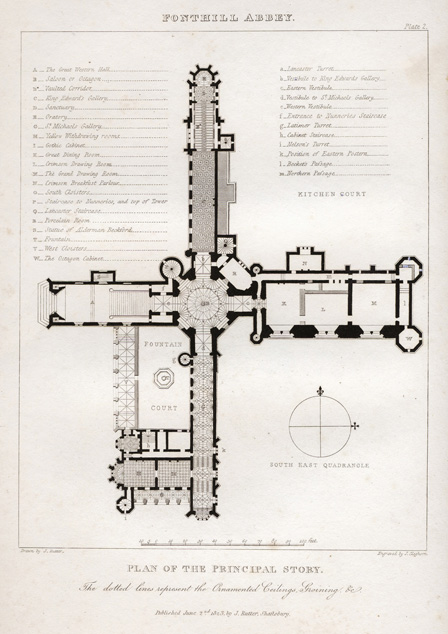

From 1806–7 the southern parts of the Abbey were refaced and Wyatt’s original compo-cement mixture that had made up the exterior walls was replaced with stone. It was a statement of intent about the permanence of Fonthill Abbey that was made more overt by the demolition of Fonthill House in 1807.113 Financial fluctuations caused Fonthill to be in a continual state of construction, with work frequently slowing or put on hold. The eventual completion of the north range in 1812 concluded a sequence of rooms through the centre of the house that created a vista over 300 feet in length. From the St Michael’s Gallery in the south, through the central octagon and into the new King Edward’s Gallery and Lancaster Tower, this vista terminated with the Oratory (Figures 4.18 and 4.19). In that final space was relocated the statue of Saint Anthony, realising an idea Beckford had been imagining since the early 1790s.

Fig. 4.18

Cross-section of Fonthill Abbey.

John Rutter, Delineations of Fonthill and its Abbey, 1823, Beckford’s Tower and Museum.

Fig. 4.19

King Edward’s Gallery looking towards the Oratory.

John Britton, Graphic and Literary Illustrations of Fonthill Abbey, 1823, Beckford’s Tower and Museum.

The completion of the north range was marked by the 1812 publication of James Storer’s A Description of Fonthill Abbey, which allowed the reading public access even if it was only access in print rather than in person, to a building and landscape that had until then been severely restricted. In his work Storer noted Beckford's intention to build a chapel in what would be the final wing of the Abbey, the Eastern Transept (Figure 4.20). The addition of this substantial new range, terminated by a pair of towers based on those at Canterbury Cathedral, was made possible thanks to an unexpected increase in income from Jamaica.114 The design was Wyatt’s but he never saw this final wing completed because, much to Beckford’s annoyance, he was killed in a carriage accident on his way to see another of his colonially funded clients, the Codringtons at Doddington Park in Gloucestershire.

Fig. 4.20

Fonthill Abbey from the South-east.

John Britton, Graphic and Literary Illustrations of Fonthill Abbey, 1823, Beckford’s Tower and Museum.

The Eastern Transept of Fonthill Abbey was intended to outshine even the Western Entrance Hall as a pseudo-Baronial space, and its design was to celebrate all the signatories of Magna Carta. It was to be the finale in the sequence of interiors designed to place Beckford and his family firmly within the annals of British history. Visitors started under the hammer-beam roof of the Western Entrance Hall emblazoned with coats of arms, and were then directed in the Oak Parlour and Brown Dining Room to the windows illustrating the pedigree of the country’s monarchy. The descent of Beckford and his wife were proclaimed through the decorative schemes, from the abbatial Gothic of the fake vaulted ceiling in the St Michael’s Gallery to the armorials and portraits in the King Edward’s Gallery. This journey through the Beckford lineage was intended to end in the Baronial Hall in the Eastern Transept (see Figure 4.21). Although completed externally the Eastern Transept was never finished internally, but its elevations provided the façade Beckford wanted to present. The Abbey, though clearly modern in construction, was an attempt to reclaim the past, allowing its owner, or as he frequently termed himself its ‘Abbot’, the romance of occupying what in his mind was the remains of a pre-Dissolution monastic house.

Fig. 4.21

Plan of Fonthill Abbey.

John Rutter, Delineations of Fonthill and its Abbey, 1823, Beckford’s Tower and Museum.

Beckford’s obsession with ancestry also revealed an important link to the history of the estate that would have helped solidify in his mind his rightful place as the master of Fonthill. While researching Beckford’s descent through his mother at the College of Arms, Isaac Heard traced a connection with Sir John Mervyn of Fonthill Gifford, a former owner of the Fonthill estate (see Chapter 3).115 Such a link allowed Beckford to claim a family connection to the estate, however distant, that pre-dated its purchase by the Alderman.

Even the completion of the Eastern Transept was not enough to keep Beckford focused, and by 1817 he talked of leaving the Abbey. How much of this intent was serious and how much just an example of his impatience or need to create something new is not known.116 In some ways it is difficult to imagine Beckford ever having been content with a completely finished project. His continual need to refit or commission new furniture allowed him to be constantly in the process of change or refinement without ever actually reaching the end. He visited Paris in 1814 and again in 1819, and continued to travel to London until lack of finances forced him to give up the lease on his London house in 1817. Unlike his father, Beckford was continually diverted from necessary attention to his business affairs and the Jamaican estates in particular; building and collecting was much more interesting. By 1821, Beckford’s debts were increasing so much that he was forced to sell many of his other properties, including Witham. Mortgages were also raised on Fonthill.117 By 1822 more drastic action was required. Beckford attempted to stave off selling the estate by offering a deal to his son-in-law, by then the Duke of Hamilton. The deal proposed that in return for the Duke paying off Beckford’s debts, covering the interest on his mortgages and providing Beckford with an annuity, Beckford would ensure that on his death Fonthill and his Hindon parliamentary seat would revert to Hamilton.118 The proposal was turned down and by the summer of 1822 the sale of Fonthill became unavoidable.

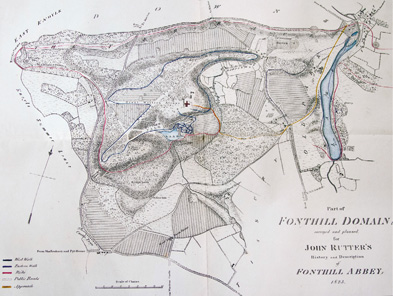

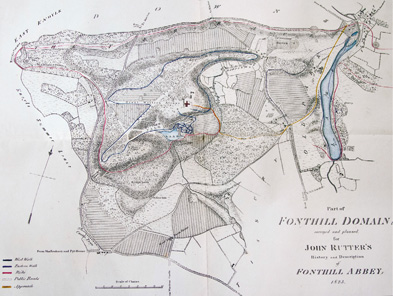

Beckford engaged Christie’s to auction the contents of Fonthill Abbey while at the same time looking for a buyer for the whole estate (Figure 4.22). Like the Fonthill House sales of the previous decade, this sale was to be the highlight of the social calendar and an opportunity for the public (at least those who could afford to purchase the catalogue and viewing ticket) to see inside a building that was shrouded in mystery.119 His plan to find a buyer for the whole estate succeeded, and at the end of the viewing Christie’s was told to cancel the auction. The Abbey, much of its contents and the whole estate were sold to John Farquhar for £300,000.120

Fig. 4.22

Map of the Fonthill Estate.

John Rutter, Delineations of Fonthill and its Abbey, 1823. Beckford’s Tower and Museum.

Beckford moved to Bath, taking part of his collection with him. The following year, Farquhar auctioned much of the contents of the Abbey and the public again had the chance to see – and this time bid for – a part of Beckford’s collection. When the architect C. F. Porden visited he predicted with ominous foresight the fall of the building: ‘would to God it had been more sustainably built! But as it is, its ruins will tell a tale of wonder’.121 This was to prove prophetic when the tower of Fonthill Abbey collapsed for the final time in 1825 (see Chapter 5).

It was in many ways wholly appropriate for Beckford’s Fonthill to come to such an end; how could the building be sustained without its ‘Abbot’ in residence?