Into the digital

These examples seem to support an analytical position in which we look at singular objects, around which swarm multiple perspectives, or interpretive positions that change according to the ethical, political and cultural frameworks that inflect museum displays. The rambaramp can be a ritual artefact, or a copy made for the market. We can see the Euphronios Krater as Italian, or as part of a universal global heritage; as art or as loot. The museum itself, as an assemblage of curatorial authority, collections history and exhibitionary technologies, brings these meanings together in very particular ways through the creation of particular subject positions.22 But what I have started to suggest through my focus on this rambaramp is that objects intervene in their own meanings in important ways, creating perspectives that emerge from material vantage points, as well as those of the museum visitor or curator. The translation of objects into digital form is a moment at which this might be made explicit, although it is too often hidden from sight in the black-boxing of digital mediation. Following Caroline Wright, we might ask at what point does the material form of an object decompose into the systems of value and knowledge that give it meaning? In digital terms, these questions might translate into asking how important is the metadata to the object? Or where does the object itself sit in the clustering of information that constitutes digital representations?

As material forms, objects such as the rambaramp can give us an interesting perspective on the digital remediation of museum collections as they are produced specifically to inspire an understanding of an ongoing process of materialisation and dematerialisation that constructs human culture and society.23 But how does this understanding of the rambaramp, a purist interpretation that focuses on the Indigenous meaning and resonance of these artefacts, an account that is reinforced within the display labels in museums from New York to Paris, mesh with an account that understands these artefacts as being dynamic players within the global relations of collecting, as part of social processes of interpretation that are strategic and work to promote some perspectives over others? How do these objects interact with the emergent global ethics and forms of governmentality that regulate their production, circulation, display and care? This conundrum, commonplace in our interpretive dilemmas around museum collections, also has the power to inform our understanding of the conceptual toolkit that we use to understand the value, resonance, permanence and even ontology of digital objects. Do digital technologies simply facilitate the conversion of data from one form into another, or do they import specific cultural forms into this process? Articulations of the ‘network society’ and the political activism of the free and open source software movement highlight the entanglements between code and law and the ways in which code has the capacity to structure specific kinds of social, political and economic operations.24 For open source coders and theorists, free software produces other kinds of liberty (the freedom to fully utilise software, the freedom to improve upon it and the freedom to understand it) as well as producing social formations that writers such as Chris Kelty have referred to as ‘recursive publics’: public spheres that are brought into being through the particular ways in which code can combine the social, technical and political in its very form.25

In my own work exploring the capacities of digital collections management systems to internalise alternative knowledge systems, I have focused on the tensions between the capacities of digital technologies to both render difference legible and to constitute a ‘neutral’ platform for the encoding of difference.26 Indigenous software projects in places such as Australia (e.g. Ara Iritija) and North America (e.g. Mukurtu – a US/Australian Aboriginal collaboration) explicitly attempt to ‘decolonise the database’ by inscribing Indigenous protocols into the form of the platform, not merely its content, replacing core classificatory schemes imported from colonial knowledge systems with local, Indigenous principles and protocols.27 Paradoxically, however, these internal reorderings of software platforms reify the ordering logics of the relational database in which everything can be flattened into networks as much as they do Indigenous knowledge systems. In turn, the management of these platforms continues to replicate some of the existing tensions and inequalities produced between curators (or technologists), visitors (the general public) and source community stakeholders.28

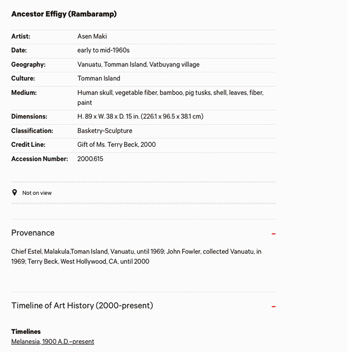

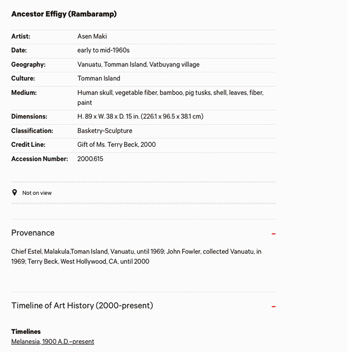

The fact that collections management systems, and the digital objects within them, have the capacity to be networked, hyperlinked and multisensorial is often obscured within the conventional ways in which they are used in museums. The facility of comparison within the relational database, the capacity of the hyperlink to create multiple pathways emanating from any one place within a knowledge architecture, or the facilities of metadata to embed multiple forms of knowledge within the same object are often muted in these digital projects. It is striking how the singular narratives and perspectives that have historically developed in museums are imported into digital projects. This is evident, for instance, in the online collections presence for the rambaramp in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.29 A search through the ‘collections’ engine provides the catalogue entry, detail on the provenance:

Figure 37

Screengrab of the rambaramp catalogue entry on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website, 1 March 2016. Provenance given: Chief Estel, Malakula, Toman Island, Vanuatu, until 1969; John Fowler, collected Vanuatu, in 1969; Terry Beck, West Hollywood, CA, until 2000. Source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/318742, last accessed January 15, 2018. Portion reproduced under fair use.

Beneath the image and catalogue data of the rambaramp in the website are links to a series of ‘related objects’, all of which are on view in Gallery 354: a helmet mask from Malakula, a slit gong drum from Ambrym, a bark ornament from Malakula and two tree fern effigies from Ambrym, mimicking the display of ritual culture that one experiences in the hall.

Here, the museum makes visible a particular perspective on the rambaramp, hiding the uncertainties contained in its own archive. The museum’s commitment to narrative is exemplified not just in the physical layout of the institution but in the website, which locates many of the artefacts with an online presence within the ‘Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History’. Just as one moves within the museum site from Ancient Greece to the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas, highlighting the timeless cultural inheritance of modern art (on the other side of the African galleries), so the website makes ‘sense’ of the collections by imposing them in a linear narrative that compresses geography and history, place and time into a narrative of linear historicity or progress.

Ross Wilson argues that one might read a museum website as a form of intertextual dialogue with the physical site of the institution. Drawing on critical code studies and digital heritage studies, he uses as an example the website for a British Museum exhibition on Ancient Egypt to argue for an ‘analogous relationship between the practices of the museum and the markup and programme languages’.30 This analogy is less straightforward than a simple translation of one knowledge system (curatorial knowledge) into another (computer code). Wilson demonstrates how the relationship between museum and visitor at the British Museum is increasingly structured as a commercial relation. He shows that this is effected by the use of a commercial search engine developed by Amazon to structure the visitor experience and create connections between objects in the website that focus on forging a relationship between like objects, targeting properties that might resonate in an Amazon search (e.g. visual qualities, visitor interaction and so forth), and structuring a visitor identity as analogous to that of a consumer in an online marketplace.31

It seems that digital systems often become analogues of their non-digital counterparts – mapping, and replicating, older representational frameworks, overwriting the capacity of the digital for radical transformation, connectivity and multiplicity with the representation of singular, teleological, narratives. What we see in many digital representations of museum collections is in fact the opposite of digital utopian discourses – museum catalogues, Google flythroughs and websites that enshrine the same issues of classification, narration, value and perspective that are on display in the galleries, and which have been on display for decades, if not hundreds, of years.

So, what might a digital system in New York look like when read through the lens of a complex ritual system in Malakula? The argument of Bowker and Star, and many others, is that classificatory systems produce, as much as they arrange, knowledge of the world.32 However, one of the reasons that the ritual systems of Vanuatu and other parts of Melanesia continue to confound is in part due to their resistance to such techniques of classification.33 The systems of status-alteration, evoked through the imagery in this rambaramp, track the social life and political authority of men and women through images, figurative (and non-figurative) forms and names that are continually fracturing and reassembling, referencing different and multiple codes of conduct and political economies. Ethnographers have found these systems notoriously hard to document, even as their efforts have become the latest way in which rank and grades are authenticated.34 Within these systems, objects, people and political systems are inherently multiple.

What are the possible implications of this for museum systems of display and representation? The stakes are high. If we return to the beginning – the encounter between the overmodelled skull and the can of coke, the visitor and the human other on display – and the ethical tensions and political inequities of representation that underscore this encounter, then we need to think about how a more expanded interpretive field alters and influences our perceptions about the proper perspective to take on these objects. Robin Boast and Jim Enote have raised a trenchant criticism of the ways in which museums have constructed the practice of ‘virtual repatriation’ (a term often used to refer to the return to communities of digital and digitised collections). They argue that ‘digital objects do not represent anything … but gain roles and capacities in their use in different social settings’.35 For Boast and Enote, digital collections are new material forms rather than simply being representations of old collections. They may reference older collections, but they should not stand in for them in their entirety. Boast and Enote challenge the indexicality, constructed through the techniques of simulation, that are increasingly built into digital visualisations of museum collections, arguing that these need to be understood as new kinds of collections.