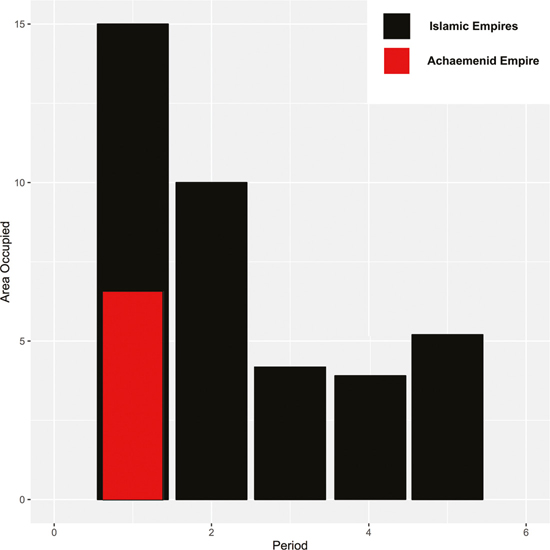

12.1 Later evidence of universalism

With the rise of the Islamic Empire and the Umayyad Dynasty in the seventh century CE, an even larger entity than before emerged in the Near East and beyond. The apogee of empires originating in the Near East was reached in the eighth century CE, when the Umayyad Caliphate stretched from Spain, and at one point Islamic armies reached central France, to India and Central Asia (Egger 2016). The cities of Samarra and Baghdad were among the largest anywhere during the Abbasid period, and may have been the largest until as late as the nineteenth century. Baghdad grew to 7000 hectares or more (Kennedy 2006: 156), possibly seven times the size of Babylon at that city’s peak in the AoE. Samarra was another of the great political capitals of the Abbasids, to the north of Baghdad, and is now one of the biggest archaeological sites anywhere, with an area of around 7000 hectares (Lassner 2000: 175).

Although the breakup of the Abbasid Empire was well underway by the ninth century CE, large political units characterized the Near East and North Africa until the end of the eleventh century CE. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the Fatimids formed an empire based on Egypt that extended into parts of North Africa and the Levant (Brett 2017). At the advent of the Crusader period in the twelfth century, the wider Near East, in particular Anatolia and the Levant, had fragmented into several small states (MacEvitt 2008: 3). This return to small, fragmented states was probably ushered in by the combination of successor competition between the Seljuks (i.e., the Sultanate of Rûm) and the influence of European Crusader conquests (Tyerman 2008). The Crusader states became political players in the region, adding a new dynamic that altered the previous political balance, and influenced competition among neighbouring states. In the late twelfth century, the rise of the Ayyubid Dynasty, based in Egypt, enabled a large state to re-emerge across areas that were fragmented. This empire, including its dependencies, stretched from Libya to Iraq at its peak. In the thirteenth century the Ayyubids were succeeded by the Mamluk Dynasty, which lasted until 1517 (Holt 1986).

With the arrival of the Mongols, and the subsequent Black Death, the population of the Near East probably declined sharply, and urban life was disrupted in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The population of Cairo, for example, was reduced, possibly by half, in this period (Lockard 2015: 292). Baghdad’s population may not have recovered fully until the twentieth century, as the city was devastated by the Mongol invasion and then the Black Death. Nevertheless, the Ilkhanate formed a large state during the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, despite major disruptions. In fact, this period ushered in the Silk Road’s last great period of relevance in international trade, which included the famous travels of Marco Polo (Barisitz 2017).

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, large areas of the Near East were conquered by the Ottomans, and for the next four centuries the Near East was often characterized by competing Iranian and Ottoman dynasties (Selvik and Stenslie 2011: 8). In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Ottoman realm stretched from Morocco to Iran and from Vienna to Somalia. However, vassal states, such as Kurdish states in Mesopotamia and Iran (the Baban and Ardalan dynasties), arose that allowed the Ottomans and the Iranians to create buffer regions and govern their wide realms more easily (Eppel 2016: 35). Throughout this period, very large cities dominated in an era of large empires. Istanbul, for example, was the peak of the urban hierarchy in the Ottoman Empire; it was a primate city in a similar fashion to cities in earlier empires in the AoE such as Antioch or Babylon (Goffman 2002). From the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, it is very possible that Istanbul was one of the largest cities in Europe and the Mediterranean region, only Cairo being anywhere close to it in population in the surrounding Near East and North Africa (Behar 2003: 1). Laws and actions were put in place to limit migration to Istanbul, as the city had become too large for the authorities to control (Kasaba 2009: 61). Movement was too easy, which allowed Istanbul’s population to spiral to a level that created difficulties in infrastructure and policing. In the nineteenth century, cities throughout the Levant, Anatolia, Syria and Iraq were closely interlinked through trade and transport, movement facilitating the intermixing of populations and the transport of trade goods (McMeekin 2010; Schayegh 2014: 36). Such links displayed social interconnectivity in the region similar to that in the AoE.

Although the Ottoman Empire’s dominance began to fray in the eighteenth century, the Near East around 1800 was still composed primarily of two large states, the Ottoman Empire and Persia, the latter of which had a succession of dynasties (the Safavid, Afsharid, Zand and Qajar dynasties). There were small states and tribal entities in the regions of Arabia, and some regions also acted as buffer states between the Persians and the Ottomans. Although smaller states did emerge, and regions in parts of the Near East sometimes lacked state authority, the longevity of the Umayyad, Abbasid, Seljuk, Ayyubid and Ilkhanate Empires, various Iranian empires and the Ottoman Empire showed the potential for very large states to continually emerge and politically dominate regions within the Near East and beyond for centuries after the AoE (