The changing nature of cities and other settlements

5.2 AoE cities

Many of the larger cities in the AoE continued to have the characteristics apparent in the pre-AoE. These include large temple districts, large palaces, city walls, gates, manufacturing areas and large residential districts. However, some important changes happened during the AoE; these were driven, at least in part, by the population movement discussed in the previous chapter that made cities noticeably different from their pre-AoE predecessors. Evidence of greater wealth and displays of power became more evident in the AoE. Not only were there much larger chief cities with far larger monumental structures and districts, but also large neighbourhoods of foreign populations began to be found. The records show that towns and cities had multiple temples dedicated to gods from distant regions. A large number of languages were spoken within cities, even as common languages developed to facilitate communication between populations. Material culture reflected not only the influence of local cultures but also that of much more distant cultures. As populations began to mix, new cultural trends, which included syncretism in art and ideas, including knowledge and philosophy, emerged. Below are descriptions of some cities that demonstrate key changes from pre-AoE cities.

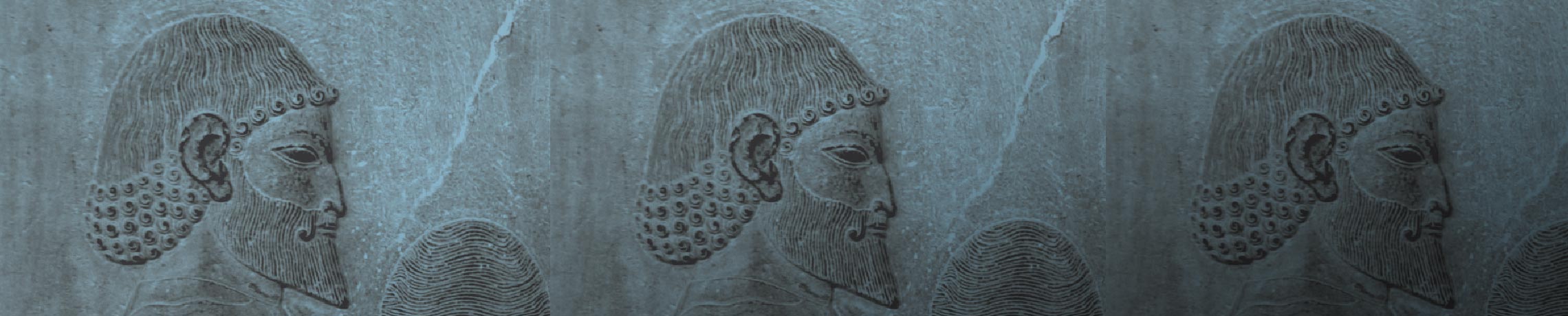

5.2.1 Kalhu, Dur-Sharrukin and Nineveh

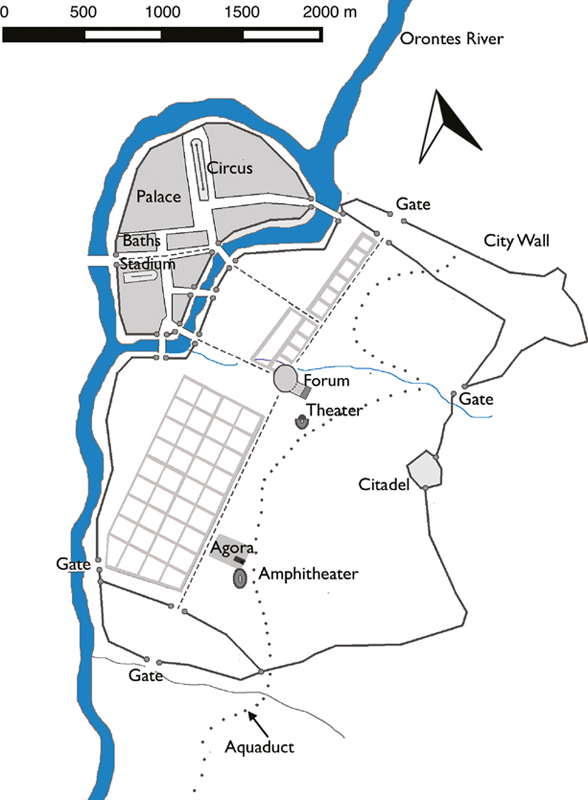

In the ninth century BCE a new type of ceremonial and capital city emerged in Northern Mesopotamia (Figure 5.9). The first of this type was Kalhu/Calah, or modern Nimrud, where the main citadel mound has been extensively investigated by Western and Iraqi archaeologists. The city was approximately 360 hectares, the main citadel being about 20 hectares (Oates and Oates 2001). In Northern Mesopotamia in the pre-AoE, it was rare for cities to be much larger than 100 hectares. The Neo-Assyrian capital cities far surpassed this limit. Furthermore, beginning at Nimrud, a new level of wealth emerged. Vast quantities of ivory, probably the greatest amount in the ancient world from a single site, have been found in the city, while the palace reliefs from the site are world-renowned. This wealth reflected the ability of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to exact or receive tribute from distant regions, that wealth being sent to the royal capitals. The royal treasures of the Assyrian queens have also been found; their splendid tombs represent a level of wealth previously unseen in royal graves in Northern Mesopotamia. These treasures indicate the reach of royal power that brought such wealth to the capital from distant regions. Furthermore, the Assyrians developed the skills to manufacture some of these luxury objects, as skills and workers from conquered territories were acquired and brought to their capitals (Oates and Oates 2001; Herrmann, Coffey and Laidlaw 2004; Hussein, Altaweel and Gibson 2016).

This pattern of wealth and grandeur continued with the later royal Assyrian cities of Dur-Sharrukin and Nineveh. Although Dur-Sharrukin was largely abandoned soon after its establishment, as Sargon II, the founder, was killed in battle, its wealth and position as a great capital are clear. The sheer size of the site, over 300 hectares, and major palaces and temples suggest a royal city that easily eclipsed most Bronze Age cities outside of Southern Mesopotamia (Loud and Altman 1938). The reliefs, such as the winged bulls (lamassu), from the site are among the largest Neo-Assyrian types. Dur-Sharrukin was eclipsed in its turn by Nineveh, which reached an unprecedented 800 hectares (Altaweel 2008). Within the city, Ashurbanipal created a royal library where scholars from Babylonia resided; the acquisition of scholarship from foreign lands, including Babylonia and Egypt, became a focus for Assyrian kings (Parpola 2007; Radner 2009). Workers, including artisans, from different areas of the empire became resident in the royal cities as they served in the construction and maintenance of some of the major monuments, including large irrigation projects and artworks (Oded 1979; Zaccagnini 1983). Although all the royal cities were very large, some of the space was taken up by new gardens that formed displays of the power and wealth of Assyrian royalty. The royal palaces, key media for wealth and power, were used to indicate Assyria’s might to Assyrians and foreigners alike (Kertai 2015). The presence of arsenals in the royal cities also made the new Assyrian capitals important armouries and bases for the Assyrian army (Reade 2011). Direct and long-distance roads – ‘royal roads’ – were longer than Bronze Age roads and helped to connect regions to the Assyrian capitals. Movement to the Assyrian capitals from distant regions became direct, and probably more rapid, as the use of horses developed (Kessler 1997; Altaweel 2008; Radner 2014a). The key characteristics noticeable in Neo-Assyrian royal cities were their wealth, the presence of foreigners, including those brought to the cities, displays of power, the aggregation of knowledge, the use of long-distance roads and sizes that demonstrated a level that began to differentiate AoE cities from the pre-AoE. By expanding into regions far beyond their homeland, the Assyrians brought both physical objects and people to their royal cities, creating the conditions for the intermixing of populations and cultural ideas.

Figure 5.9

The Assyrian royal cities of (a) Nimrud, (b) Dur-Sharrukin and (c) Nineveh. Temple, palaces and arsenals indicated (Kertai 2015; after Zunkir 2015a, 2015b; Fredarch 2016)

5.2.2 Babylon

Babylon, which was already a great city by the second millennium BCE, perhaps as large as 500 hectares (Gibson 1972), reached nearly 1000 hectares during the Neo-Babylonian period, by the sixth century BCE (Figure 5.10). The city probably extended far beyond its city walls. Similarly to that of the Neo-Assyrian cities, the scale of the ceremonial, religious and palatial areas became far larger than in earlier periods. The temple of Ésagila and its enclosure alone, dedicated to the chief Babylonian god Marduk, occupy approximately 15 hectares. Babylon became the ceremonial, economic and political capital, reflecting not just its power but its central role in the Babylonian state and society (Koldewey 1914; Unger 1970; Jursa 2009; Seymour 2014: 9). Even after the fall of the Neo-Babylonian state, the city’s importance continued for some time, until the Hellenistic period after the fourth century BCE, after it had served as one of the Achaemenid capitals. The presence of foreigners in Babylon and throughout Babylonia was already prominent in the Neo-Babylonian period, when Elamites, Egyptians, West Semites, Arabs and probably others from around the Neo-Babylonian Empire’s territory, became evident in textual sources (Zadok 1979, 1981; Moukarzel 2014: 144). People either came to Babylon voluntarily or were brought forcibly. The exile of the Jews, mentioned in the Bible, brought another foreign element to Babylon, and much of this community remained in Iraq until the early 1950s CE. By the Achaemenid period, the Jewish community was thriving; it contributed to the rise of prominent banking and landholding corporations such as the Murashu, who were able to conduct business in various Babylonian cities (Stolper 1985).

As Babylon became very large, not only did it become an increasingly ethnically diverse city, but also the various cultural groups had opportunities to thrive socially. In the pre-AoE, Babylon incorporated foreigners such as Amorites and Kassites; however, in the AoE the diversity was probably greater or from more widespread regions, and there were opportunities for these groups to express their ethnic makeup. In the Seleucid period a Greek community was established, adding further ethnic diversity to the already diverse population. The presence in the city of a Greek theatre and gymnasium, among other structures, shows foreign and distant influences on Babylon (van der Spek 2009). Cultures expressed at Babylon did not simply reflect Babylonian elements, as they may have done in the Bronze Age, but the presence of various Near Eastern elements and, later, Greek elements began to be reflected in the city’s architecture and material remains.

Figure 5.10

Babylon’s inner city indicating major structures and temples. The Greek theatre and the large temple of Ésagila are indicated (after Micro 2006)

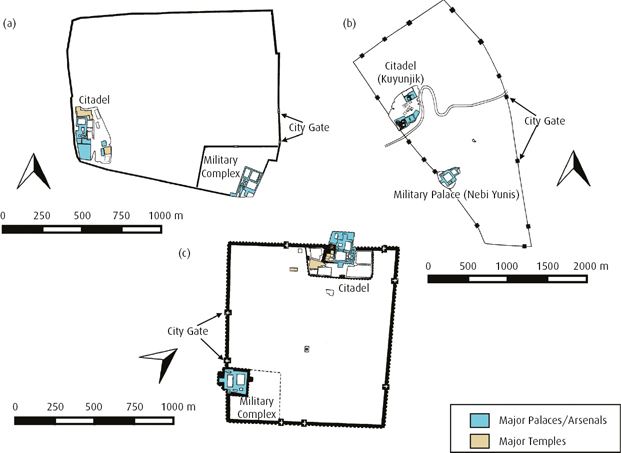

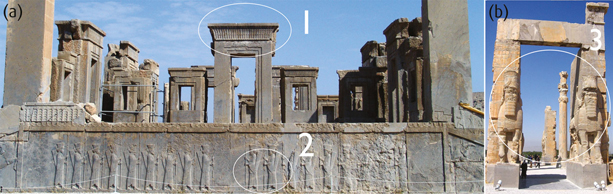

5.2.3 Persepolis

The trend towards ceremonial capitals, seen in the Late Bronze Age, appears again in the Achaemenid period with the construction of Persepolis in the late sixth century BCE (Figure 5.11). While it is not clear how large the city was, several characteristics that contrast with those Bronze Age centres are evident. A remarkable aspect of Persepolis is the multiple iconographic and architectural elements incorporated within the central royal district and its key structures (Figure 5.12; Root 1979). Within 100 years of the collapse of the Neo-Assyrians, the multi-ethnic character of the Persian Empire had become evident, as we see in its remains today. Specific structures, such as the Apadana, demonstrate the incorporation of various populations which were paying homage to the Persian kings. Egyptian-style gateways, Hellenistic-style flowing robes and Assyrian-style winged human-headed bulls (lamassu) are among the artistic and architectural elements. In fact, Persepolis is not portrayed as having been founded only by Ahuramazda, the Persian god, but ‘all’ the gods are stated in the foundation inscription from the city to have participated (Schmidt 1953; Mousavi 2012; Babaie and Grigor 2015). It was not intended to be a city just for the Persians, but a place that represented the varied populations within the empire of the Achaemenids. Paradise, as envisioned by the Achaemenids, was embodied in the architecture and gardens of their royal cities (Boucharlat 2001). Included in this ideal were the multitudes and diverse populations found in their realm.

Persepolis began to represent the idea of universalism, in which people from different regions were symbolically united through the representation and presence of their gods in the metaphysical sense, but also in an earthly way through the architecture and art of the city. The architectural intent may have been to demonstrate a type of ‘voluntary’ subordination, as Khatchadourian (2016: 114) suggests, but the message was to display the diversity found in the city. This contrasted greatly with earlier Bronze Age and Iron Age cities and their iconography, in which the triumphant king was generally shown as being superior to his vanquished foes. The emphasis in pre-AoE cities was on the local, chief gods, while at Persepolis the inclusion of ‘all’ the gods represented the Achaemenids’ different view, which incorporated others in their triumph rather than displaying them as victims. In Persepolis’ reliefs, foreigners are not shown as inferior or vanquished but as individuals who supported and praised the Achaemenid king: they provide gifts to the court rather than having those items forcibly taken from them (Figure 5.13). Although the art at Persepolis certainly reflected official propaganda, where content foreigners came from different parts of the Achaemenid Empire (Dandamaev, Lukonin, Kohl and Dadson 2004: 293), the emphasis on inclusion of, rather than triumph over, foreigners indicates that the official message had begun to shift. Real policy implications became evident at places such as Persepolis. Foreigners are attested to have been based at Persepolis, including by texts from the Persepolis Fortification Archive (PFA). These foreigners included Arabs, Cappadocians, Indians, Babylonians, Bactrians, Egyptians and others who were civil servants or professionals who may have stayed temporarily, or lived permanently, in Persepolis and other royal cities, such as Susa. Languages in the PFA include Greek, Phrygian, Aramaic, Elamite, Persian and Babylonian (Stolper 1984; Dandamaev et al. 2004: 293). The population diversity at Persepolis may have been foreshadowed at Pasargadae under Cyrus, where foreign influences are evident. Evidence from Pasargadae suggests that foreigners, including Babylonians and Lydians, were incorporated into the population, and stylistic syncretism is evident in the art (Stronach 1997; Briant 2002: 77–8).

The very strategy of Achaemenid kingship, emphasizing the integration of foreign populations under the unifying power of the Achaemenids, was symbolized by Persepolis. Darius, Xerxes and some of their successors even use the title ‘king of lands (or nations) containing all sorts of men’ to show this diversity (G. Cameron 1973; Stolper 1984). At Persepolis, it is the foreign influences in the art and architecture and the incorporation of varied populations and their gods within the city that differentiate it from its pre-AoE predecessor ceremonial cities such as Dur-Untash and Amarna.

Figure 5.11

Plan of Persepolis, indicating some of its well-known structures (after Pentocelo 2008; Mousavi 2012: 10)

Figure 5.12

Reliefs from Persepolis found in the Palace of Darius ((a) Kawiyati 2007) and the Gate of All Nations ((b) Farshied86 2006). Numbers 1–3 indicate Egyptian, Hellenistic and Assyrian influences

Figure 5.13

Depiction in the Apadana of foreigners bringing wine to the Achaemenid court (Maiwald 2008)

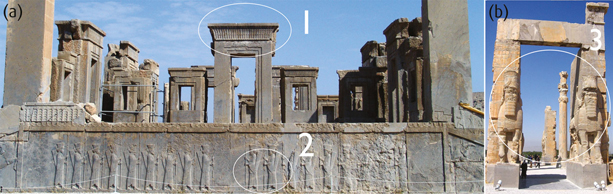

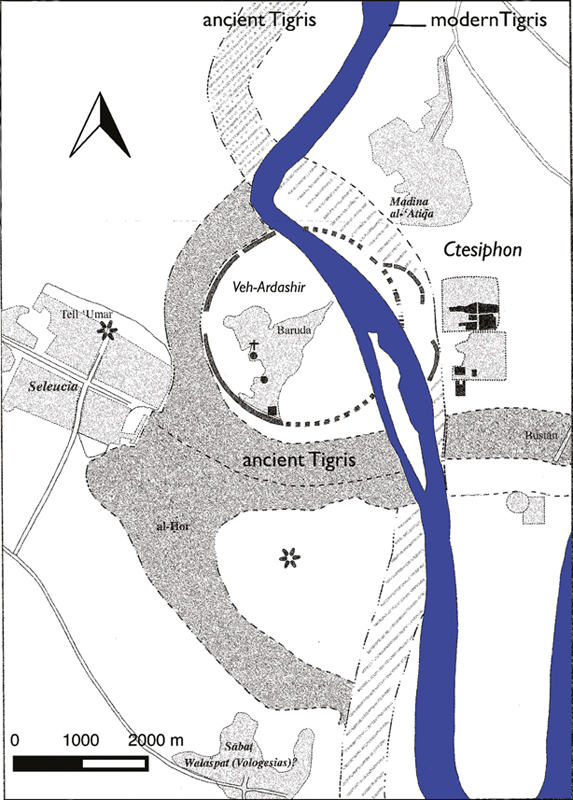

5.2.4 Ctesiphon

At one time perhaps the largest city, or more accurately urban zone, anywhere, ancient Ctesiphon (Figure 5.14), about 35 km south of modern Baghdad’s centre, served as one of the great capitals of the Parthian (Arsacid) and Sasanian states (ca. 247 BCE–651 CE). By the late Sasanian period, the cities in this urban zone were Aspanbur, Veh-Ardashir, Hanbu Shapur, Darzanidan, Veh Jondiu-Khosrow, Nawinabad and Kardakadh. However, it is likely that only four or five of these districts had large populations; some of the names may refer to the same place (Morony 2009; Davaran 2010: 59). Ctesiphon is best known for its famous archway, the largest freestanding vault until the last century, which is a remnant of a monumental Sasanian palace compound. The exact dimensions of the city are difficult to determine with certainty, and it is possible some of the site is missing because of erosion by the Tigris, but the city seems to have merged with Seleucia, the Seleucid capital, which was located nearby. Some of the districts and cities were created, in part, by deported populations; together they formed the area known as al-Madāʾen (Invernizzi 1976; Negro Ponzi 2005). This made Ctesiphon and its urban region part of a heavily populated urban zone that may have contained a population in the hundreds of thousands (Ṭabarī 1989). Although the walled area of Ctesiphon is about 550 hectares, an estimated 1500 hectares is a reasonable estimate for the maximum extent of Ctesiphon and its urban environs. Given the effects of erosion, of the multiple urban districts, and of the site, or more accurately sites, not having been fully surveyed, this estimate is plausible (Lee 2006: 157).

Relevantly for demonstrating how such large cities came into being during the AoE, the population consisted of various ethnic groups, including Greeks, Persians, Jews, Assyrians, Arabs, Arameans, Babylonians, Syrians, Romans and probably others. In the Sasanian period, religions represented within the city included Judaism, Christianity and Zoroastrianism, while other cults existed, at various periods, of other gods that were associated with the various population groups (Ṭabarī 1989). The population therefore reflected the type of primate city the AoE helped to produce: it was a disproportionally large population made up of various ethnic groups, some of which had migrated or been brought to Southern Mesopotamia from distant regions; they included people who had arrived during earlier periods or in the lifespan of the city. Religion in the city represented the wide diversity of the population rather than just the local or regional beliefs. Large-scale manufacturing, dependent on foreign products from more distant parts, was increasingly important in the Sasanian period to large cities, where glass making and other production thrived, as it became possible to obtain resources from distant regions (Simpson 2014: 204). Great wealth flowed to Ctesiphon through long-distance trade, and the position of the city on the Silk Road routes allowed products from China and Europe to come to the city (Wagstaff 1985). Access to the Tigris and canals would have enabled it to benefit from seaborne trade from the Arabian Sea. Long-distance connections, easy movement and connections to international trade helped the surrounding countryside thrive economically and increase in population and population diversity, while the urban region itself developed into a major political and economic centre.

Figure 5.14

Map of Ctesiphon and its urban region (after Lencer 2007; Negro Ponzi 2005: 167)

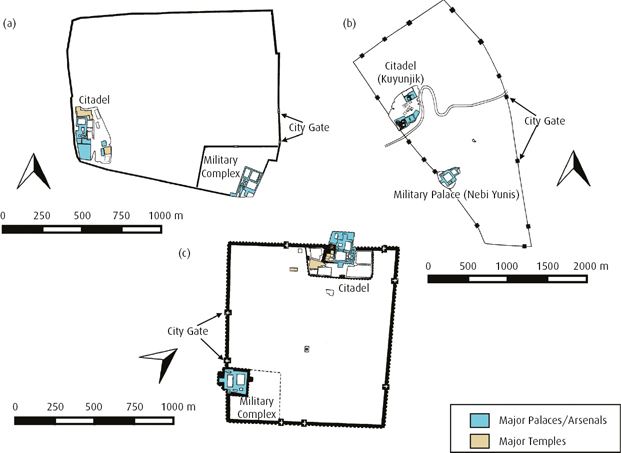

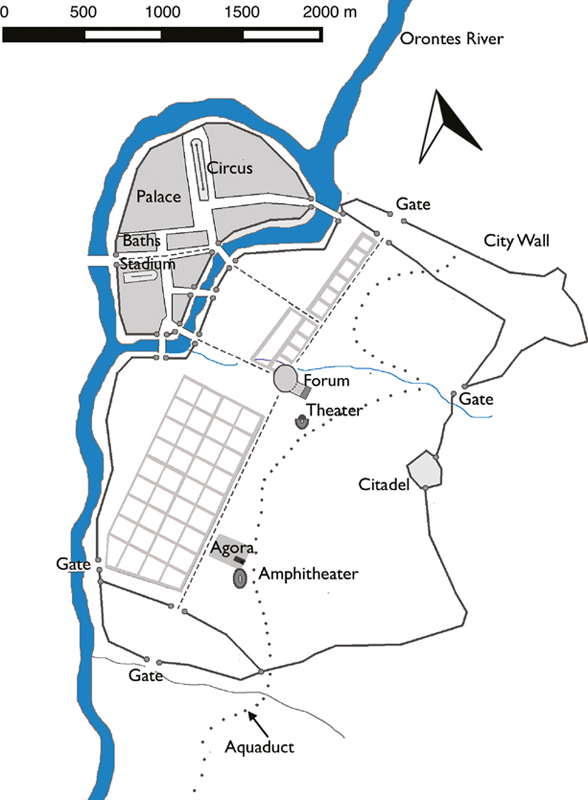

5.2.5 Antioch

One of the great cities founded at the end of the fourth century BCE was Antioch on the Orontes (Figure 5.15). The city was established in a Hellenistic grid layout by Seleucus I. Much of the city is now underneath modern buildings or buried by sediment; however, it has been partially reconstructed from ruins and from historical texts. From its beginning, the city had a diverse population composed of people from the surrounding region in the Northern Levant, but also of Jews, Macedonians and Greeks (Malalas 1986). Antioch appears to have been founded as one city in a tetrapolis of Seleucid cities in Syria, the others being Laodicea, Apamea and Seleucia Pieria. It became a capital in the Seleucid period. By the Roman period, it dominated the Eastern Mediterranean coast economically and culturally, far surpassing its nearby rivals in size and economic weight (Sandwell and Huskinson 2004).

Although the exact population is unknown, it is clear that the city was very large and had a diverse population in the Roman period. A reasonable estimate of the population is in the order of several hundred thousand; the city became one of the primate cities that greatly surpassed other Mediterranean cities (De Giorgi 2016: 180). The area of the city may have been only about 200–300 hectares during the Seleucid period, but it was far larger in the Roman/Byzantine period (Aperghis 2004: 93; Cohen 2006: 93). This growth probably contributed to its rise as an early seat of Christianity and a major centre for Judaism, which probably further diversified the already diverse population. Within the Christian community in the city, for instance, were missions from Armenia, Greece and Latin-speaking regions. The universal faiths began to use large and diverse cities such as Antioch as new bases, even though those cities had little to do with the origins of those faiths. Additionally, many temples to Greco-Roman gods, including Jupiter and Artemis, were found (Downey 2015). Large cities such as Antioch had influence that stretched over three continents. In the Roman period, although primary texts from Antioch itself are scarce, texts from other regions indicate the existence of individuals who identified themselves as having come from or lived in Antioch and its region. These include people from North Africa, southeast Europe and the Near East (De Giorgi 2016: 175). People were migrating to and emigrating from the city across many regions, and commerce from other cities throughout the Mediterranean and elsewhere became directly linked to the city.

Figure 5.15

Conjectural representation of Antioch (after Cristiano64 2010; Downey 1974: Fig. 11)

5.2.6 Alexandria

The best-known city founded by Alexander after his conquest of Egypt ca. 331 BCE is Alexandria. While the city’s Jewish, Greek and Egyptian populations are well known, during the Ptolemaic period Syrians, Medes, Persians and other Asian populations also lived in the city. By the Roman period, if not earlier, various populations from different parts of Europe were intermixed with the already cosmopolitan population (Vrettos 2001: 7). In the first century BCE, the city was perhaps the second largest in the Roman Empire and served, through its great harbours, as the commercial entrepôt for the Eastern Mediterranean (Strabo 1967: book 17.1.31; Haas 1993: 234). Throughout its history in the AoE, Alexandria was an astounding mix of cultural ideas, ethnic groups and religions (Hinge and Krasilnikoff 2009). The intermixture of so many population groups made the city not only cosmopolitan but also a great example of how universalism transformed the urban makeup of primate centres in which a variety of cultural expressions and syncretism in art and ideas were found together. Whereas in the pre-AoE Egyptian thought and culture dominated, as in Amarna, in the AoE the cultural landscape became much more varied, even in respect of common material culture. Syncretism is expressed through the variety of artistic, theological, philosophical and religious ideas prevalent in the city, such as the worship of the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis (Figure 5.16) or the philosophy of Philo. Greco-Roman and Egyptian art and architecture commonly became fused (Vrettos 2001; McKenzie 2010). Such variety in ideas and material culture reflected the mixtures of cultures that were prevalent and the fact that they were able to intermix freely as they resided together.

Although it is not well preserved today and has been built over in many places by the modern city, our knowledge about Alexandria has been preserved in historical works. There were several unique structures during the history of this city, such as the lighthouse in Pharus. One of the best-known structures was the library of Alexandria, which functioned as part of Alexandria’s Musaeum, an institution devoted to scholarly activity (Stephens 2010). The library epitomized the spread of knowledge and information as travel and movement encompassed greater distances and became more direct during the AoE. Galen speaks of ships having to unload their written works to the library for copying. From what scholars can reconstruct, the library contained not only Greek and Egyptian knowledge but also knowledge originating from Babylonia. Although earlier cities, such as Nineveh, had established libraries, to which knowledge and scholars were brought from different regions, the knowledge held at Alexandria originated from even more diverse places and came to be collected in a central repository (MacLeod 2004; Potts 2004a; Barnes 2004). Alexandria’s library showed that knowledge and learning became more mobile in the AoE.

Figure 5.16

The god Serapis (above), a syncretized Greco-Egyptian god, was worshipped in the Serapaeum, or temple to Serapis, at Alexandria (Nguyen 2009)

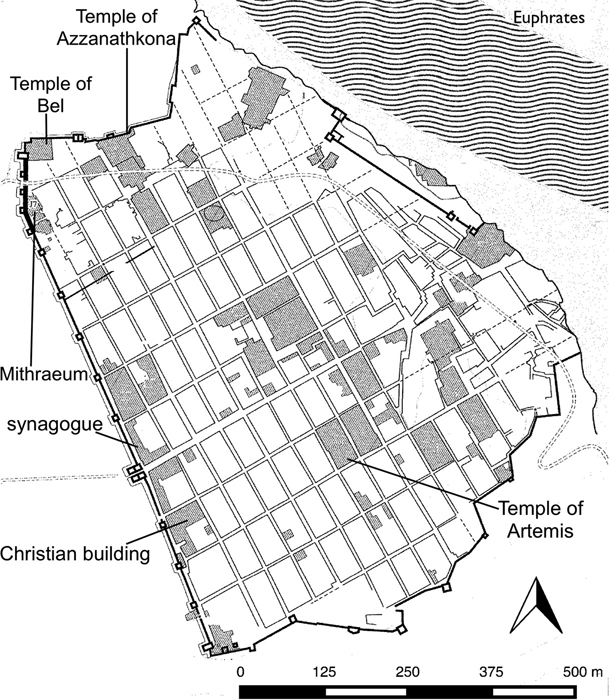

5.2.7 Dura Europos

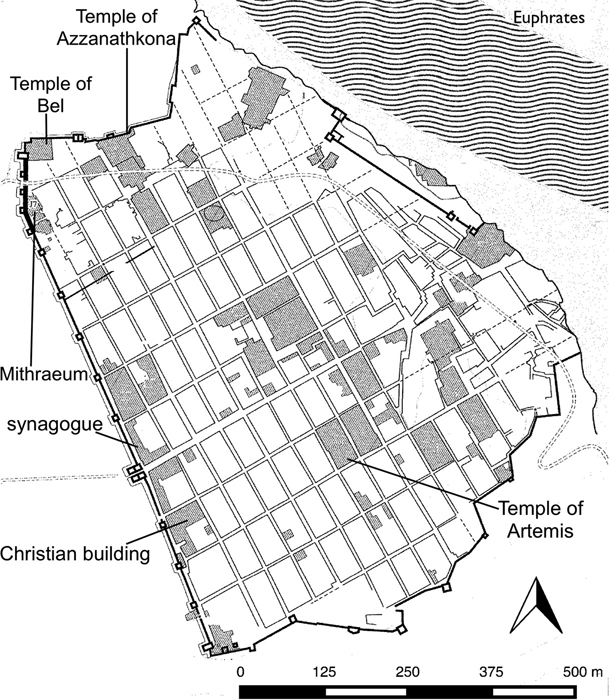

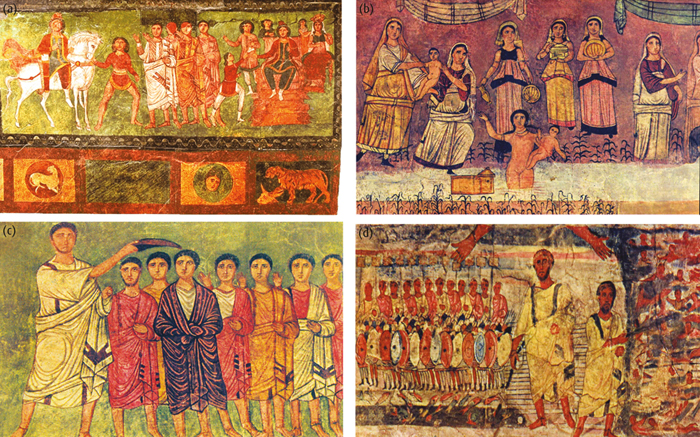

The town of Dura Europos (Figure 5.17), which has a Hellenistic-style grid layout, is found along the Euphrates in southeast Syria near the border with Iraq. The town was founded ca. 300 BCE and lasted until ca. 256/257 CE, the year in which it was destroyed by Shapur I (Matheson 1982). The site is small in comparison with the larger cities of the AoE, such as Alexandria and Antioch, as the city walls enclosed an area of only 75 hectares. At this time, as stated earlier, many of the great cities of the region were to be found along coastal areas or along major waterways, particularly in Southern Mesopotamia. Nonetheless, Dura Europos had many of the characteristics of a cosmopolitan city similar to the major urban centres that became more international. It contained places of worship for Jewish, Christian and polytheistic religions originating from Greco-Roman, Near Eastern and Indo-Aryan regions. Places of worship also contained temples dedicated to syncretized Greco-Near Eastern gods. The languages spoken and written in Dura Europos during the Roman period reflected the ethnic diversity found in the town: they included Aramaic (including Palmyrenean, Hatrean and Syriac), Hebrew, Parthian, Persian, Arabic, Greek and Latin (Kaizer 2009: 235). The famous art known from the town, including tempera wall paintings in the well-known synagogue (Figure 5.18) and church, indicates a mixture of local Semitic/Near Eastern and Greco-Roman stylistic influences, including dress and iconographic symbols from these varied cultures (Perkins 1973; J. Baird 2014). In short, the mixture of languages, cultural symbolism, religions and art styles reflects how people and ideas from distant regions came to characterize smaller towns such as Dura Europos and not simply large cities.

Figure 5.17

Site plan of Dura Europos showing areas excavated (shaded). Areas uncovered include important religious structures from various religions and dedicated to Christian, Jewish, Roman, Near Eastern, Indo-Aryan and syncretized Greco-Near Eastern gods (after Marsyas 2016a; Gelin 1997)

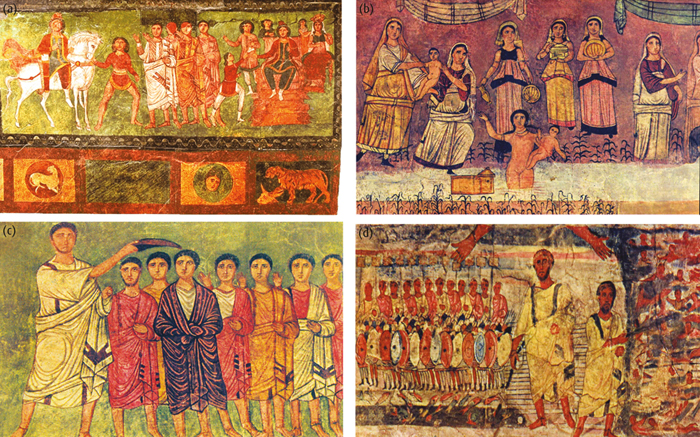

Figure 5.18

Examples of tempera wall paintings from the synagogue found at Dura Europos. Scenes a–d are: (a) from the Book of Esther (Duraeuropa 2016; (b) Moses being pulled from the Nile (Becklectic 2016a); (c) David anointed by Samuel (Marsyas 2016b); (d) the Exodus (Becklectic 2016b)