11 Valentines, the Raymonds and Company material culture

Valentines Mansion’s EIC owners and their material objects

During the eighteenth century three owners of Valentines were involved with the East India Company: Robert Surman (c.1693–1759), Sir Charles Raymond and Donald Cameron (c.1740–97). Robert Surman, Deputy Cashier of the South Sea Company in 1720, spent a short time in prison when the South Sea ‘Bubble’ burst but survived with £5,000 and purchased Valentines in 1724. He does not appear to have been unduly tainted by the Bubble and returned to banking, becoming a partner in Martin’s Bank and later founding his own bank, Surman, Dineley and Cliffe. He invested in the East India Company, managing the ship Sandwich. In 1754 he sold the house to Charles Raymond, a retired EIC captain who managed many voyages for the EIC and became a respected figure in the City.2

Raymond was a successful captain whose profitable voyages in the Company’s service played a key role in his emergence as a man of wealth and fortune. Much of the profit gained by men associated with the Company derived from the private trade goods brought home by the captains and officers of East Indiamen. On his second voyage as captain of the Wager 1737/8 (i.e. the ship left England in the winter of 1737/8), for example, Charles Raymond earned £3,100 in this way. However, while his ship was being prepared for the return journey he was free to work with local agents and he deposited rupees with the East India Company’s accountant in Bengal for which he was later paid £3,000 in London. Raymond’s earnings in trading privately thus earned him at least 30 times the salary paid to him as the captain (approx. £200).3

Sir Charles Raymond was Valentines’ most important link with the EIC and the material goods from Asia, which so decisively shaped Georgian domestic interiors. Valentines is not a grand house, but it was nonetheless a family home, which boasted many exotic, luxurious objects. It is important as a lonely survivor in East London of the type of home described by Sylas Neville in 1785 as ‘the small but neat box of the retired East India captain’.4 The Sun Fire Office insurance documents illustrate the increase in value of the contents of Valentine House during Raymond’s occupancy (1754–78). The value of insured goods rose from £500 in 1755 with the household goods insurance tripling to £1,500 in 1769, with an additional £500 for china and glass.5

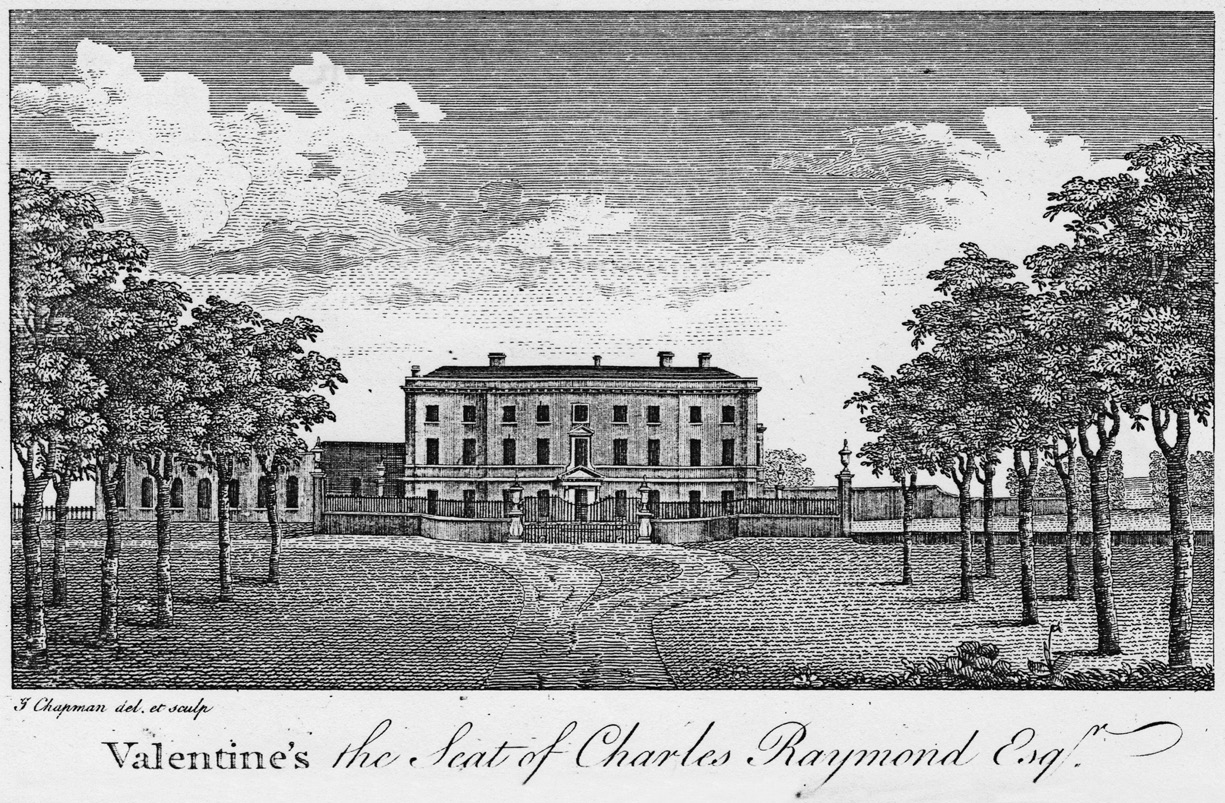

Figure 11.2

Porcelain plate decorated with the arms of Charles Raymond and his wife, Sarah Webster. China, c.1760. Private collection. Image courtesy of Georgina Green and Heirloom & Howard Ltd.

Domestic luxury goods produced in Britain figured among Sir Charles Raymond’s purchases for Valentines: during Raymond’s tenure, the original of William Hogarth’s Southwark Fair was at Valentines, probably one of several works of art in which Raymond invested his fortune. But goods from Asia were especially conspicuous among the material objects recorded as belonging to Valentines during Raymond’s day. An extant porcelain plate bearing his arms (see Figure 11.2), demonstrates that, like many other East India Company captains and officials, Raymond commissioned an armorial porcelain dinner service from China.6 Similarly, Valentines also contained a book presented to Raymond by Captain Josiah Hindman, who served as first mate when Raymond was captain of the Wager and went on to captain the ship when Raymond retired and became the principal managing owner (PMO).7 The book, which is large and bound in leather, was hand painted in China.8 It contains a series of 814 watercolour illustrations of plants and insects found in China, with Chinese and English captions detailing their medical use. While porcelain and books from Asia may have been regarded as commonplace, especially by the second half of the eighteenth century, other objects received greater attention as particular curiosities. In 1771, for example, the author of a history of Essex claimed that Valentines ‘may, with great propriety, be called a Cabinet of Curiosities’.9 Although it is difficult to know the extent of Raymond’s collection, we do know he gave a neighbour a piece of sculpture of a hard, dark marble, which had been brought home from the Island of Elephanta.10

As Raymond sought to fill Valentines with Asian objects and curiosities, he also set to work extending the structure of the house. In 1769, he made significant changes to Valentine House, adding a bay and raising the roof. In 1771 the building was described as ‘one of the neatest, and best adapted of its size, of any modern one in the county; its ornaments are well chosen, and the grounds belonging to it laid out with great judgement and taste.’11 The external appearance of Valentines today is much as it was at that time. Raymond enhanced the gardens, which had been created by Robert Surman. In 1758, he planted a black Hamburg vine, which became very prolific, and a cutting was taken to Hampton Court Palace. The cutting has achieved greater fame than the parent plant which died late in the nineteenth century. 12

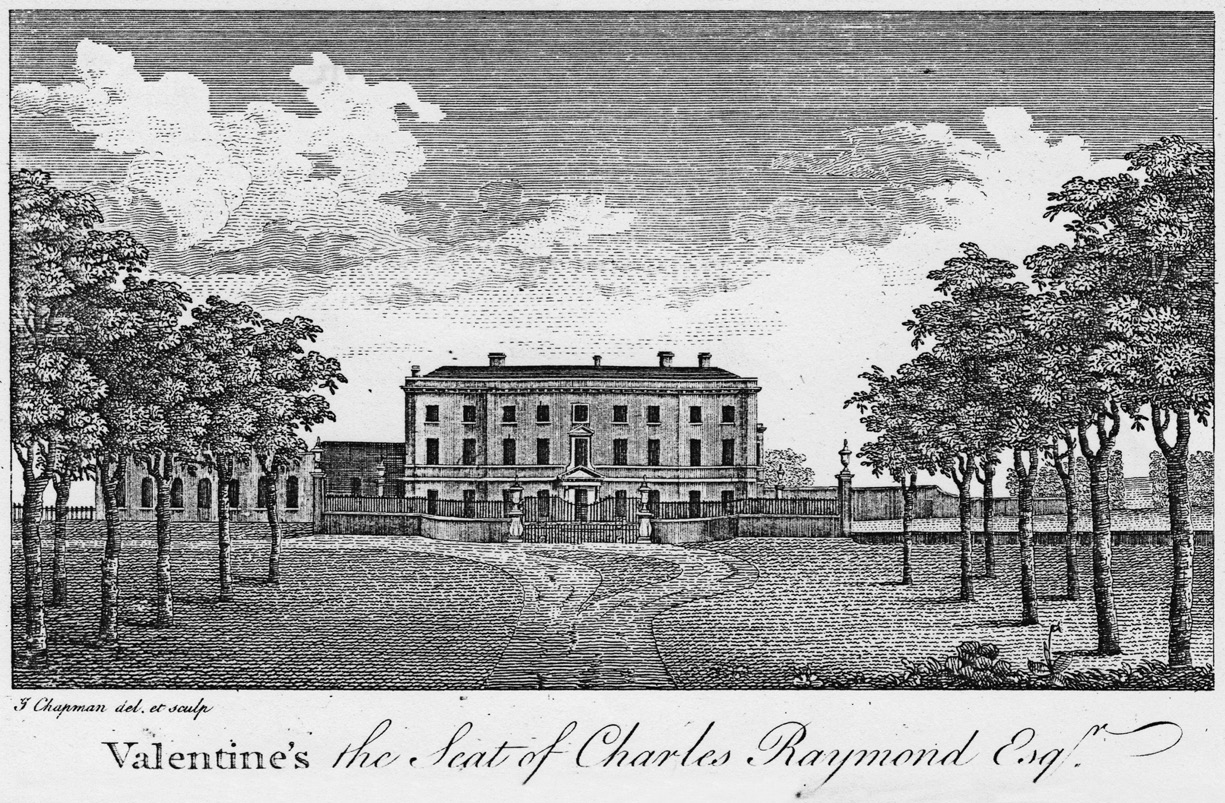

Figure 11.3

A New and Complete History of Essex by a Gentleman vol. 4 (1771), 276–79. This image shows the orangery, situated to the left of the house.

Imports from the East adorned not only Valentines’ interiors but also its gardens. Both Robert Surman and Charles Raymond came to live at Valentines when they had small daughters, and it is not hard to imagine the girls growing up, playing games and walking in the gardens as they grew older. In Raymond’s time there was a conservatory or orangery beside the house, which would have given them an elegant and sheltered place on colder days (see Figure 11.3). The orangery could well have housed plants brought home from Asia. Like the Oriental luxuries with which wealthy Georgians furnished their domestic interiors, gifts of exotic flora and fauna were integral components of the material exchanges that oiled the wheels of the Company’s patronage and which helped maintain close ties among members of the Company’s far-flung family networks.13 The orangery and gardens might also have held the ‘curious birds and other animals, from the East Indies’ that George Edwards, FRS, mentioned seeing in August 1770. Edwards described a new species of bird, which he called a ‘snake-eater’, known today as a secretary bird. His letter says that a pair of birds was brought home but one died soon after it was landed. From the description given by Raymond’s servant, it was thought to be a male of the species. The birds must have been caught when an East Indiaman (possibly the Granby) called in at the Cape (South Africa) on the way home.14

With Asian imports adorning the house both inside and out, its interior and exterior features stood as testament to Raymond’s travels, trades and networks. When Charles Raymond died in 1788, the future of the house and the objects that filled it was decided upon by a lengthy, legalistic will. It ensured his eldest grandson would be provided for, and he left a small amount to his sister-in-law Elizabeth Webber, but otherwise his property was to be divided between his two surviving daughters, Sophia Burrell and Juliana Boulton.15 By this means, two women who had themselves never voyaged to the Company’s territories became custodians of Raymond’s Indian collection. Raymond’s eldest daughter, Lady Sophia Burrell, became a writer and poetess. She married William Burrell, grandson of Charles Raymond’s uncle, Hugh Raymond, who had served as EIC captain and later PMO early in the eighteenth century. It was Hugh Raymond who ensured Charles had a good introduction to the sea and acquired the new ship Wager for him in 1734. In default of male issue, William Burrell was named to inherit the baronetcy granted to Charles Raymond on 4 May 1774.16 Sophia’s two younger sisters Anna Maria Newte (who died in 1781) and Juliana Boulton, also married men closely connected with their father through the EIC. The youngest, Anna Maria, married Thomas Newte who was also a second cousin but through Charles Raymond’s mother. He had come up through the ranks of the EIC to become captain and later PMO, working in close association with the Raymond family. Sadly Anna Maria died in 1781, two years after they were married.17 Juliana, the middle daughter, married Henry (Crabb) Boulton, the son of Richard Crabb who had sailed alongside Charles Raymond as a fellow captain and who also became a PMO. Richard’s brother Henry Crabb had served as a senior clerk with the EIC and later became a director. Both brothers took the name Boulton from their cousin Richard Boulton who was connected to the EIC for 40 years, and left property to Henry, which later passed to his brother Richard.18

After Raymond’s death, Sophia and Juliana sold Valentines and many of its contents to the third of its Georgian owners with EIC connections, Donald Cameron. He came from an ancient Scottish family and in 1763 had married Mary Guy, a step-sister of Charles Raymond’s wife. By 1778 he was working at the banking house of Sir Charles Raymond and Co. where he later became a partner. He took over the management of several East Indiamen in association with Charles Raymond. Cameron had been living at a property owned by Raymond, immediately to the south of the Valentines estate, later known as Ilford Lodge. In 1791 Cameron served as Sheriff of Essex but by the time he died in 1797 the bank had suffered serious losses due to the French revolution and Valentines and its contents were sold with the other property he owned in Ilford to meet the debts.19 An advertisement for the auction, featured in the St James’s Chronicle, lists some of the ‘Valuable Effects’ that Valentines contained in 1797 and demonstrates its rich interiors.20 The details of the sale include paintings by eminent masters, prints and drawings, oriental articles and fine ornamental china, a library of books and a considerable quantity of fine wines. As the advertisement attests, by the later eighteenth century, Asian luxuries were fully integrated with English objects d’art in the homes of Company families in Ilford.