The Amhersts and familial belonging

Like the history of Touch House, the history of Montreal Park was marked by lapses of succession, imperial disappointments and collaborative family endeavor. Jeffrey Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst (1717–97) originally built Montreal Park in the 1760s, to mark both his return from America and his Canadian successes as commander-in-chief of British forces. This home passed to Amherst’s nephew, William Pitt Amherst (1773–1857), in 1797. Like his uncle, William Pitt played a variety of important (yet often unsuccessful) roles in global affairs.39 Despite his lack of success on the international stage, however, in 1823 Amherst was appointed to the role of Governor General of India. Accompanied by his wife Sarah (1761–1838) and their eldest son Jeffrey (1802–26) and daughter Sarah Elizabeth (1806–76), Amherst travelled to India and began what would become a highly problematic tenure as a colonial governor. He declared war with Burma in early 1824, and mounted an attack on Rangoon. Two expensive years of fighting only yielded the territories of Arakan, Tenasserim and Assam. In 1828, Amherst returned home to Britain with his wife and daughter, his son having died in India.40 Soon after returning to England, the Amherst family began rebuilding their country house, Montreal Park in Riverhead, Kent.

Maintaining a shared identity across imperial space was an important but endless task for the Amhersts. As several historians have observed, imperial families keenly felt the distances placed between different members and developed a range of strategies to traverse spaces of absence.41 Correspondence and gift-giving, for instance, went some way to mediating a sense of family belonging over time and space. William Pitt Amherst’s daughter Sarah Elizabeth was an active correspondent, who sent sketches as well as letters while in India between 1823 and 1828. In 1824, for example, she wrote to her brother Frederick (1807–29) – who had remained in England – and included a detailed set of five sketches showing their primary residence from several different angles in the hope that he would ‘better to understand the local situation of Government House’. These sketches were accompanied by written notes, which further described details represented in the drawings. Sarah Elizabeth asked that Frederick not keep the sketches to himself, but rather share them with their half-sisters Maria and Harriet to show ‘how the flower garden is laid out’.42 She thus encouraged her brother to respond to the sketches as he would do letters, as a form of communication that could be shared and read communally.43

The Amherst family also developed other techniques through which they could create and recreate a sense of family across distance. They employed journals to recount experiences and events, which other family members then read at a later point. On her younger brother Frederick’s return from Italy in 1829, Sarah Elizabeth recalled how she ‘read with the greatest pleasure & admiration his journal in Italy – it was so neatly kept & his account of every thing he saw so good & clear’.44 While scholars have long understood letter reading as a shared and communal practice, less attention has been given to similar practices of journal reading, but this remained an important strategy for the Amhersts and others, such as the Clives.45 When in India between 1823 and 1828, Sarah Amherst and her daughter Sarah Elizabeth both used journals to record their journeys to and experiences of India. Sarah wrote a total of seven journals beginning in 1823 with their journey to India and ending with their return to England in 1828, while Sarah Elizabeth wrote four journals covering the years 1820 to 1842. Sarah Elizabeth’s reading of Frederick’s journal suggests that her own (and her mother’s) journals were produced with a particular audience in mind and actively participated in reaffirming a sense of familial belonging when read by others on their return from India. Significantly, through the emphasis placed on reading journals in Britain, these practices suggest at the importance the Amherst family placed on reconstituting a sense of familial belonging once physically present and returned home.

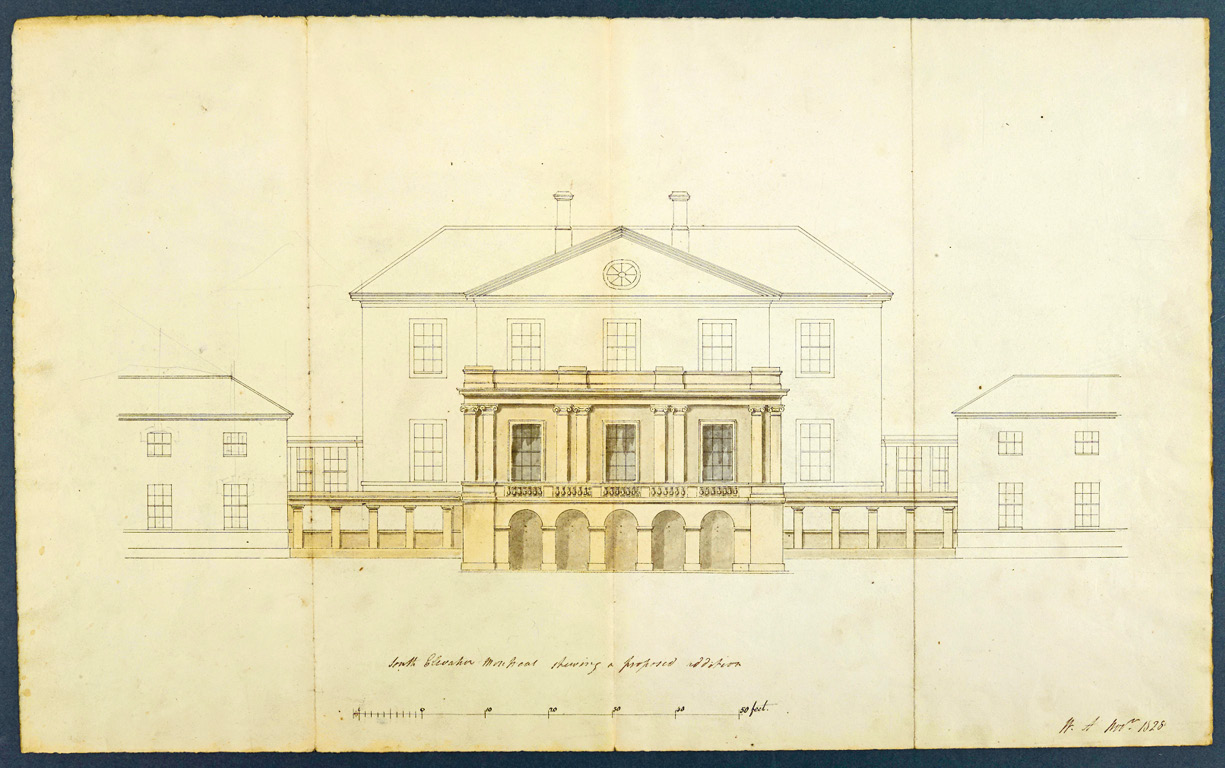

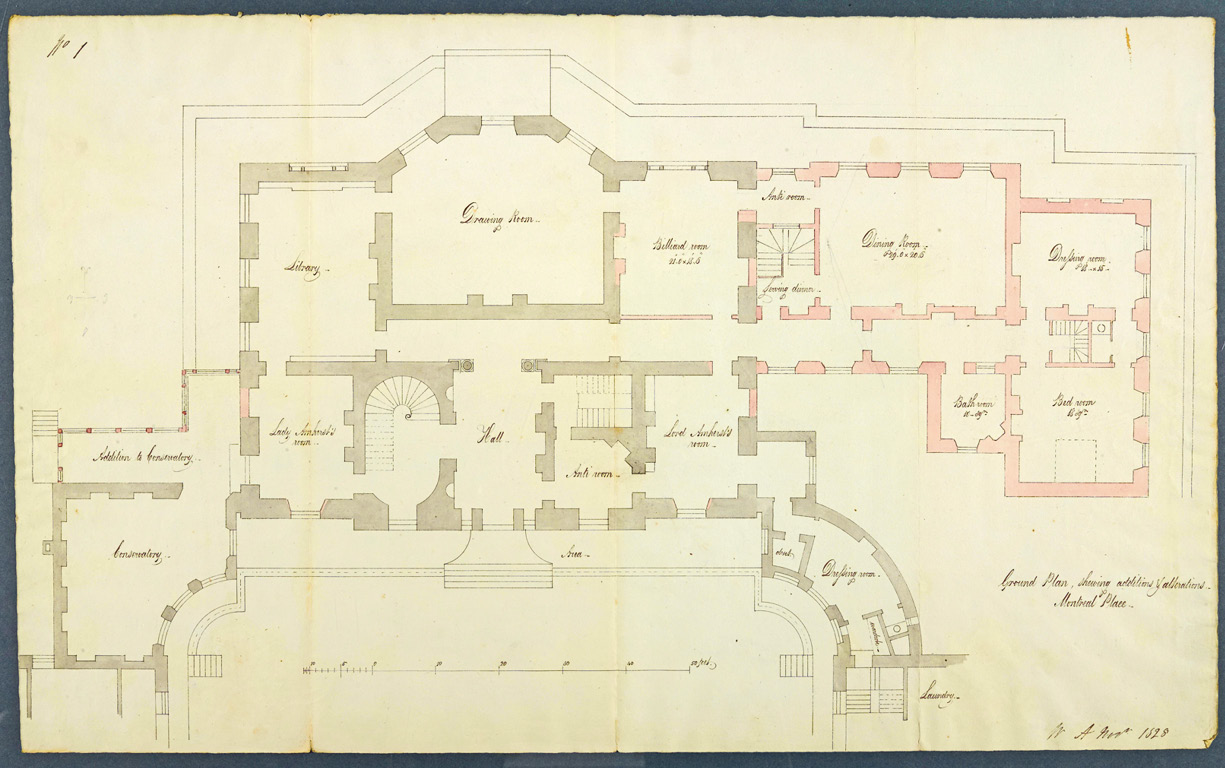

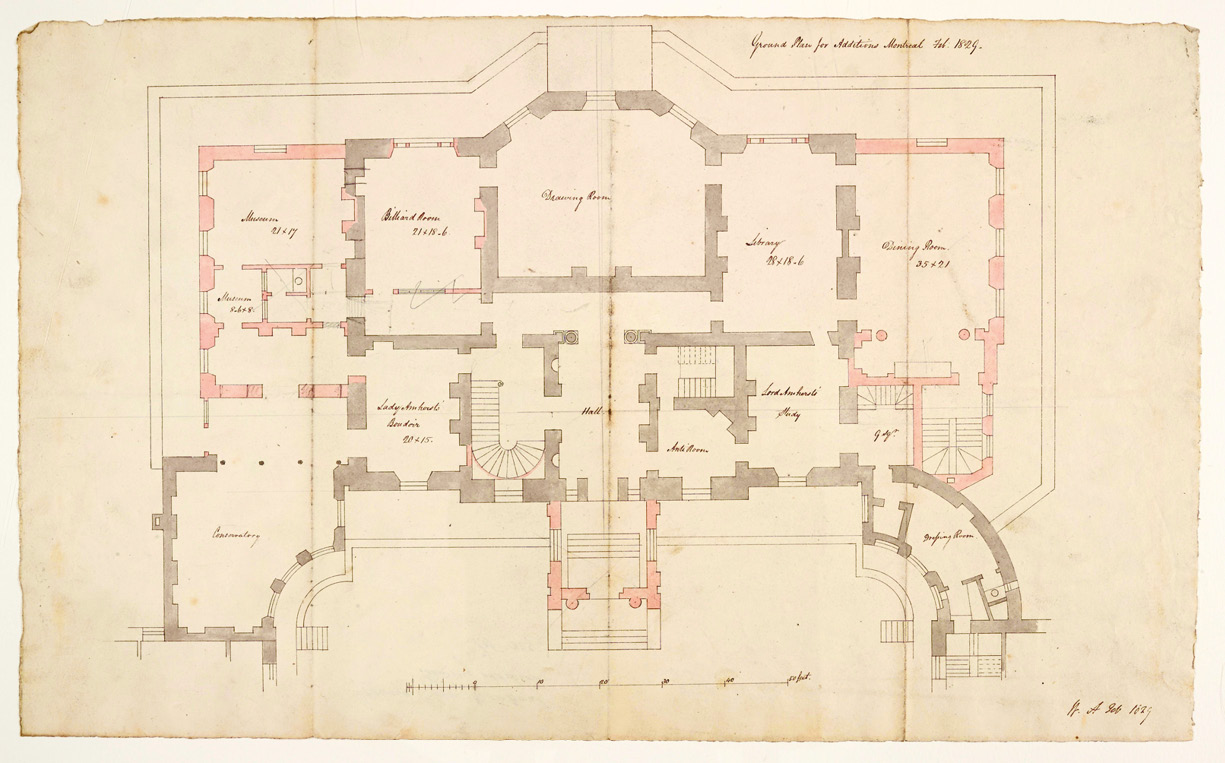

After returning to England in 1828, the Amhersts initiated other projects to restore their sense of familial identity, most notably by refashioning their country house, Montreal Park in Kent. At one level, domestic refashioning can simply be understood as an attempt to render in material terms the new wealth and status they had acquired in India. Certainly on making the decision to go to India in the winter of 1822–23, the economic benefits that might accrue from service featured highly in their discussions. They asked their acquaintances and friends for advice on whether the post would be economically and emotionally worthwhile, and their advisers suggested that although the emotional costs might be high, the economic gains justified this dislocation. More particularly, acquaintances suggested that the Indian post would ultimately allow their male children to prosper – ‘only consider what an advantage a few score thousand pounds will be in setting up these Lads’.46 In addition to wealth, moreover, while in India, Amherst also managed to acquire new status. In 1826 William Pitt had been created 1st Earl Amherst of Arracan and Viscount Holmesdale, honours that moved the family up a rank within in the peerage. Yet, despite having reasons to embark on the materialization of power and wealth through house building, the new house created by the Amhersts remained relatively modest. Significantly, in the 1970s, the 5th Earl Amherst simply described Montreal as ‘a comfortable Georgian house’ (see

In 1829 the Amhersts commissioned the architect Atkinson to draw up plans for a substantial extension to accommodate a billiard room and new bedrooms and dressing rooms for Lord and Lady Amherst.48 Notwithstanding their employment of Atkinson, the Amhersts actively involved themselves with the design process and conceived it as a collaborative act. In her journal, William Pitt Amherst’s daughter Sarah Elizabeth, described how before they hired Atkinson, they spent much time working with a scale model of the house and its proposed extension. She described how they ‘had a model of it in wood, with a moveable additional form, to be placed where one chose, but on every side it looked like an excrescence & deformity’.49 The family took the unusual step of providing themselves with specialized tools through which they could consider different solutions to the problem of creating an extension at Montreal Park. The construction of a scale model of the house and the proposed extension suggest at the time and effort they invested in the building process.