Archaeologies of Media and the Baroque

Codices

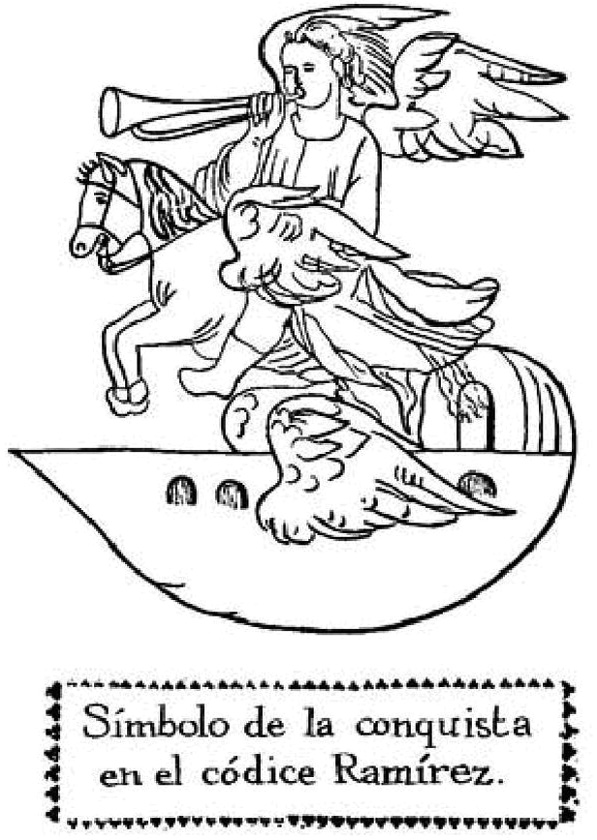

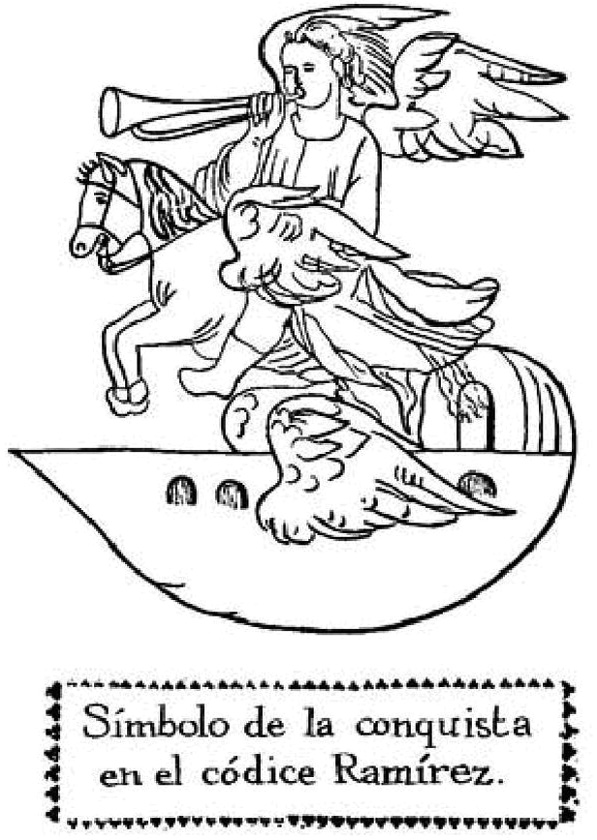

The second baroque medium interrogated in Operación Bolívar is the image-text itself, constructed here as a diverse collage of different systems for combining texts and images. These range from illustrated manuscripts (complete with historiated initials, marginalia and miniature illustrations), atlases and newspapers to advertisements, instruction manuals and digital on-screen displays used in aerial combat and videogames, as well as the comic’s own conventions of text captions and speech bubbles. In particular, the book develops a parallel between Mesoamerican codices and their role during the post-Conquest period and the function of the graphic novel in the context of late book culture.38 This association is introduced in the first paratextual insertion in the Caligrama edition, a blank page with a line drawing of a winged angel on horseback announcing its arrival on a trumpet, which is accompanied by a text panel describing it as a ‘símbolo de la conquista en el códice Ramírez’ (symbol of the Conquest in the Ramírez codex; see Fig. 3.5). The page introduces the dominant themes of the narrative but also points to a more structural analogy between the graphic novel and the post-Conquest codex that is developed over the course of Operación Bolívar. The direct citation from the Ramírez Codex coupled with the wider structural parallels draw attention to the nature of both the post-Conquest codex and the graphic novel as transitional texts. The former embodies a moment of transition between pre-Columbian and European Renaissance epistemes and the latter occupies a strategically transitional position between print culture and the digital realm. The Ramírez Codex, entitled Relación del origen de los indios que hábitan esta Nueva España según sus Histórias (Account of the Origin of the Indians who Inhabit this New Spain According to their Histories), was compiled in the late sixteenth century by the Jesuit priest and ethnographer Juan de Tovar. The book is believed to have been based partly on the work of Dominican friar Diego Durán and partly on the work of sources written in Nahuatl by indigenous Aztecs who had converted to Christianity shortly after the Conquest. Post-Conquest codices, such as the Ramírez Codex, are transitional texts in the sense that they encode a confrontation between incompatible Mesoamerican indigenous and Catholic-European systems of knowledge. The Ramírez manuscript’s role in interpreting indigenous cultures for the purposes of conquest makes it an active agent in the colonial imposition of lettered Renaissance culture that Walter Mignolo traces in The Darker Side of the Renaissance.39 The book is in many ways complicitous in the subordination of pre-Columbian pictorial forms of record-keeping to European systems of textual documentation. Although the Ramírez Codex echoes the conventions of pre-Conquest codices by including images created by indigenous informants, these images are all effectively subordinated in relation to the written word. Whereas pre-Conquest codices combine text and image in a non-hierarchical fashion, the images in Tovar’s work are safely contained in a separate section of the book in which the only textual intrusions are explanatory labels. As Serge Gruzinski explains, by the 1570s when Tovar was working, textual labels had become ‘the prime vector of information’ and thus ‘represent the triumph of the book’.40

Fig. 3.5

Symbol of the Conquest from the Ramírez Codex, reproduced in Operación Bolívar (Edgar Clement)

However, despite their ultimate role in the epistemological colonization of indigenous cultures, the post-Conquest codices also embody a moment of transitional instability. The process of archaeology carried out by Operación Bolívar emphasizes this instability by constructing both the codex and its inheritor the graphic novel as a space of conflict for competing epistemes and the scopic regimes that embody and naturalize these epistemes. Lois Parkinson Zamora argues that post-Conquest codices are ‘inordinate’ baroque documents that integrate ‘contradictory ways of seeing’.41 Pre-Columbian systems of visual representation assert themselves against attempts by scholars such as Tovar to incorporate them into European Renaissance modes of visual knowledge through the segmentation of images into panels and the use of explanatory labels. In his analysis of the Ramírez Codex, J. H. Parry points out that, if most of these books were never allowed to be published, it is clearly because they were perceived to be dangerous by the prevailing political powers.42

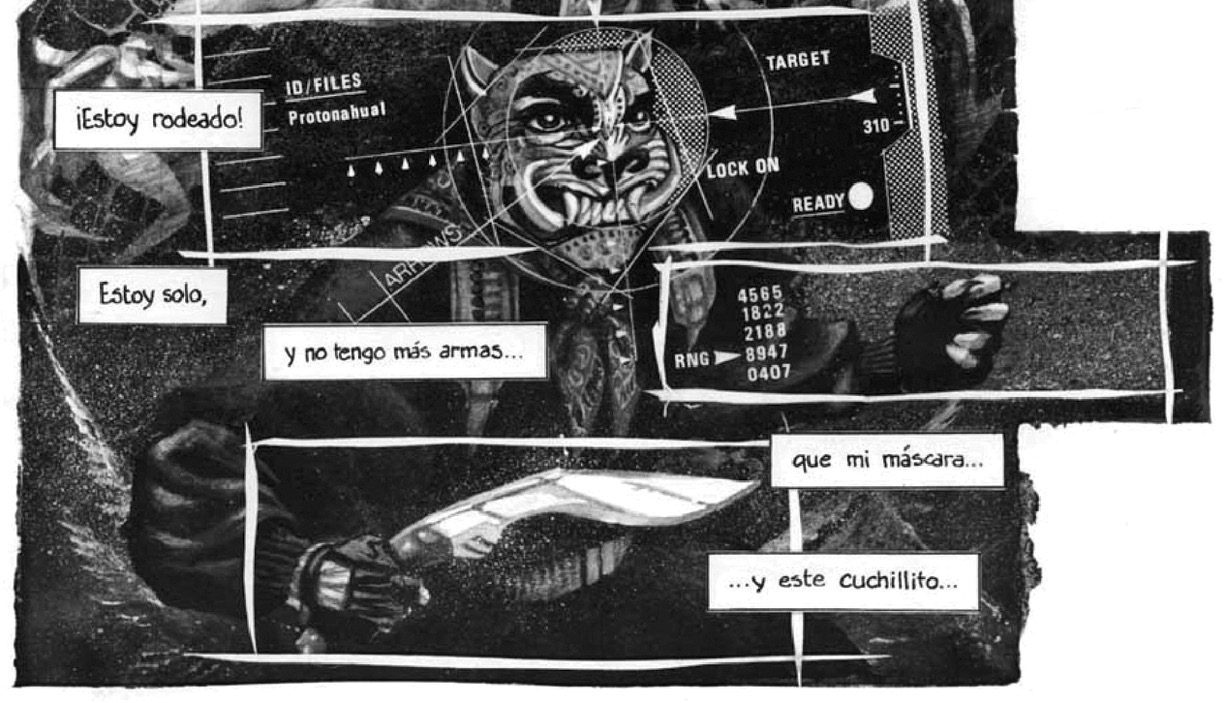

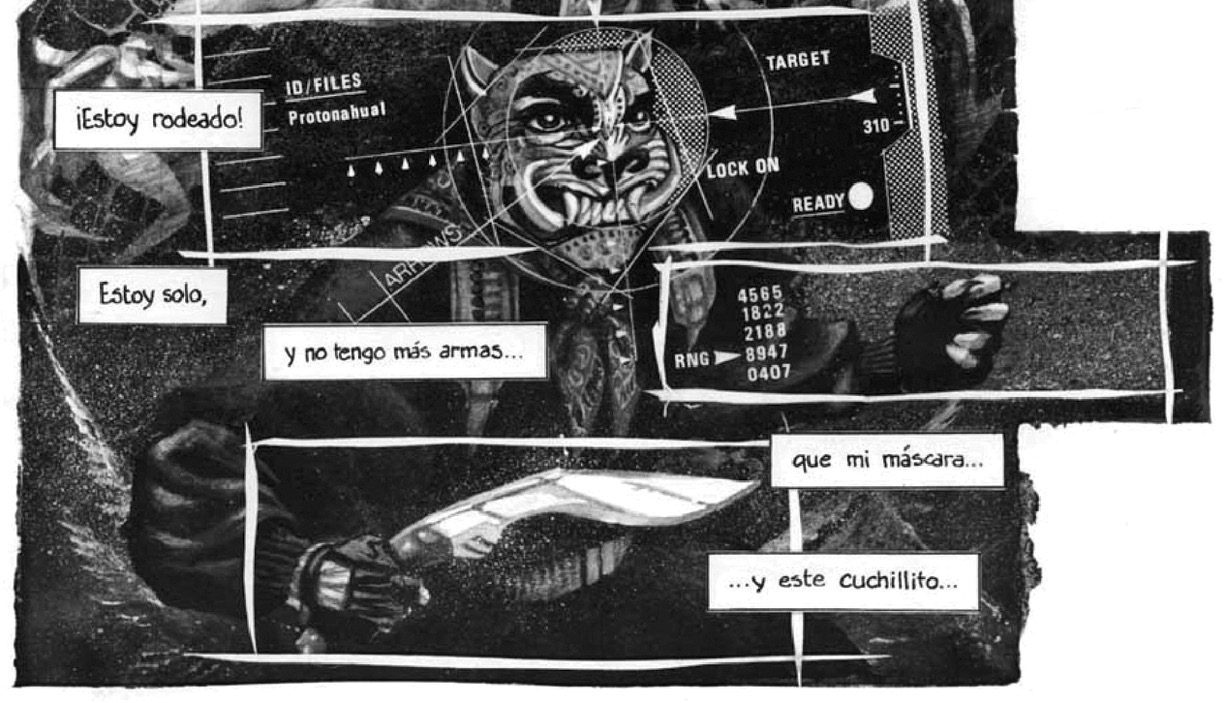

In a way that echoes this dynamic, Operación Bolívar occupies a transitional space between print and digital cultures. This is firstly evident in the distribution strategies employed by Clement. As well as print versions such as the Caligrama edition studied here, the book has been made available as an online PDF in an embrace of digital distribution that foreshadows the more extensive use of online platforms for Los perros salvajes (see Chapter Two). Secondly, the transitional status is emphasized at the level of narrative in the book through tensions between what Martin Jay describes as the ‘scopic regimes of modernity’.43 On the one hand, the book repeatedly reproduces an instrumentalist, technological mode of envisioning. This is introduced in the first pages of the novel through the use of anatomical diagrams and is reinforced throughout the book in the form of technologically detailed drawings of weaponry. During the fight sequence at the end of the book a panel depicts Román, who has morphed into a nahual, seen through one of the CIA’s helicopter gunsights (see Fig. 3.6). In this respect, the book itself embodies a militaristic mode of vision. Through the direct connection between anatomical drawings and hi-tech digital weapons guidance systems, Operación Bolívar draws attention to the hidden epistemic violence inherent in scientific modes of seeing that present themselves as neutral, objective and natural.

Fig. 3.6

A nahual seen through a gunsight in Operación Bolívar (Edgar Clement)

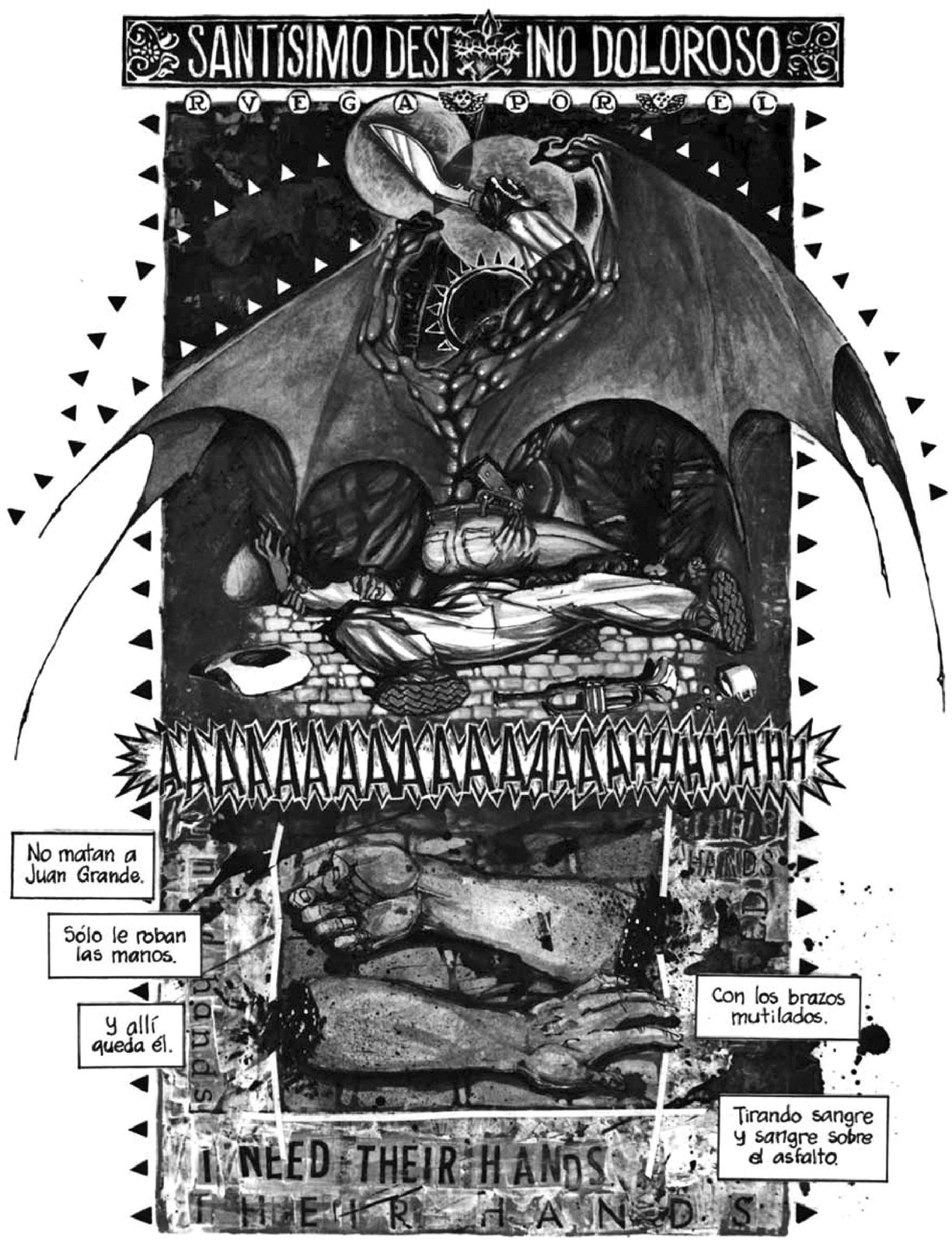

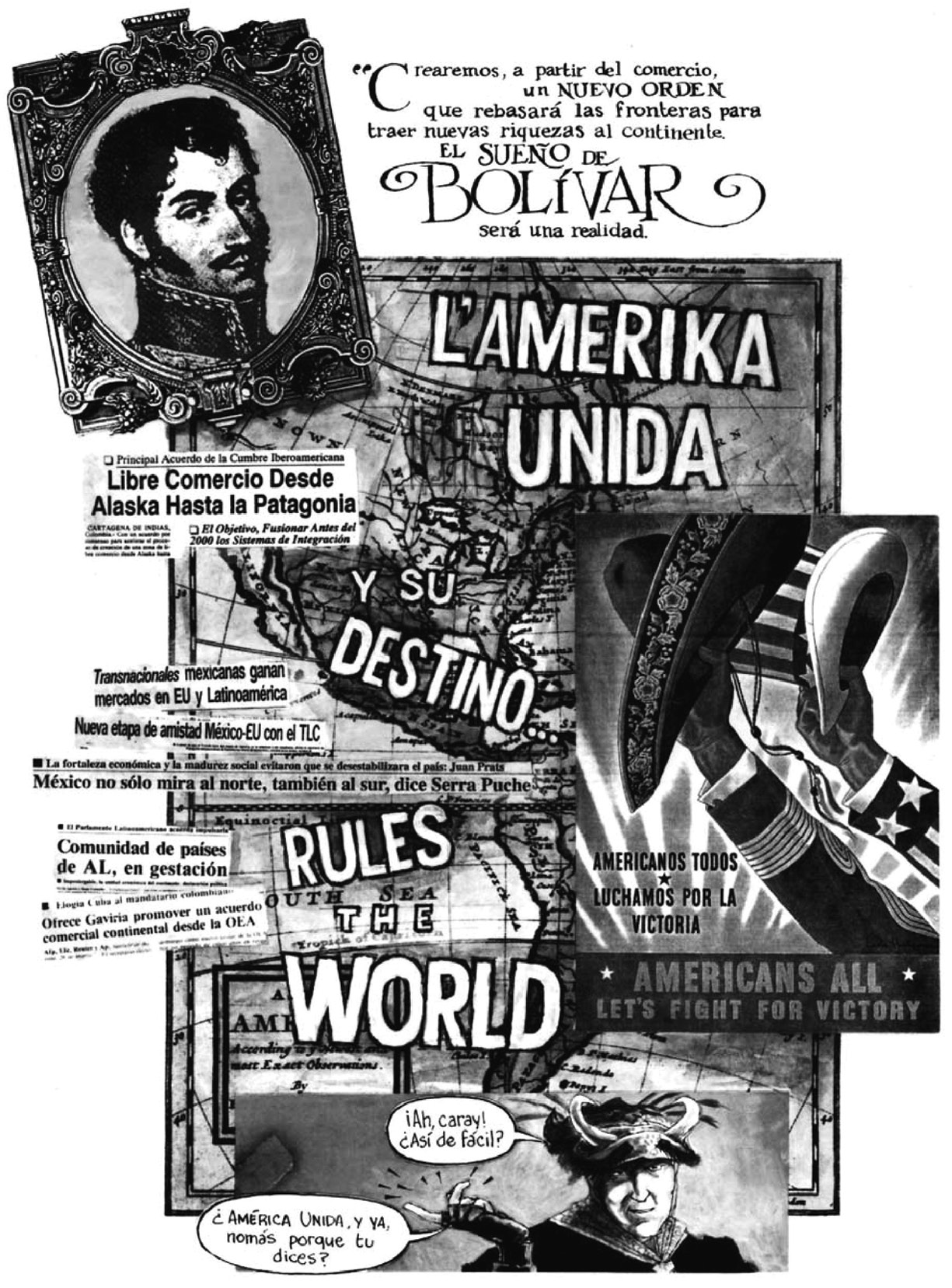

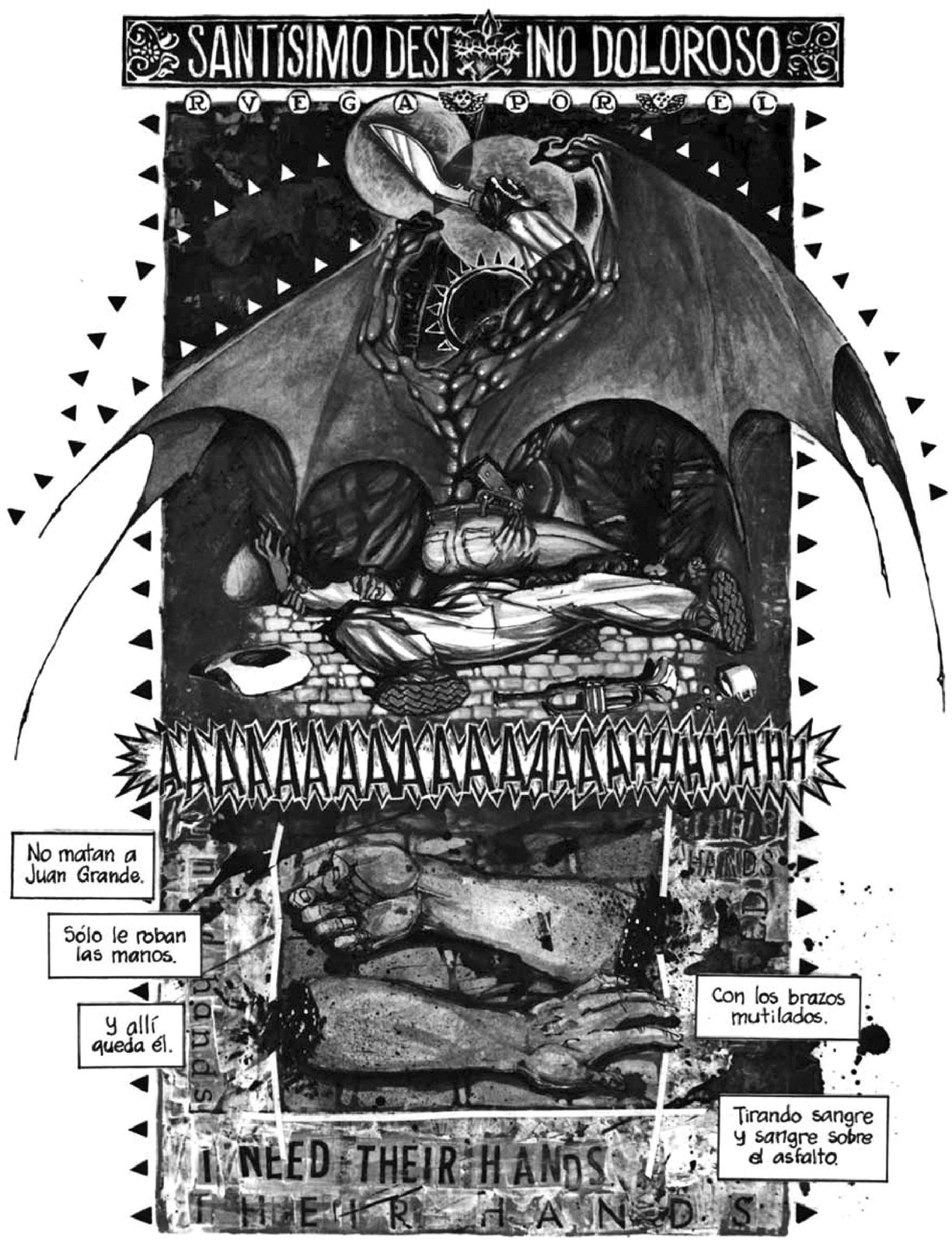

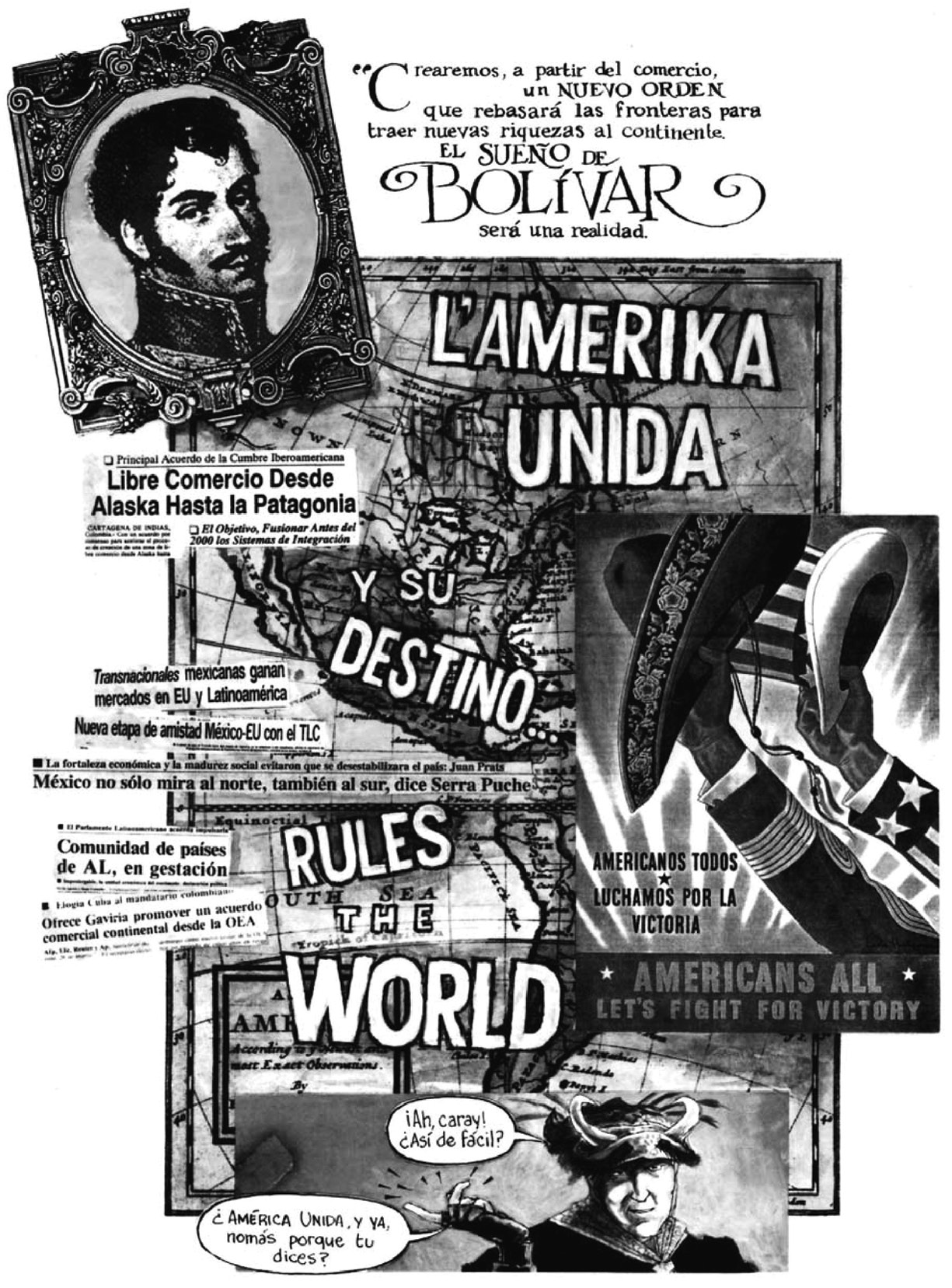

However, the book also stages the limits of mechanistic Cartesian vision by confronting it with a baroque scopic regime, which Jay describes as a ‘moment of unease in the dominant model’.44 The book stages a baroque undermining of Cartesian vision through an emphasis on multiple fragmentary perspectives and an often bewildering excess of imagery drawn from different media and historical contexts. The relationship between the panel and the page in Operación Bolívar echoes the blurring of boundaries between architecture and art, structure and façade in the baroque aesthetic. As Helen Hills puts it, ‘In the baroque, masses spill over, overflow; matter is uncontainable’.45 There are no clear distinctions between diegetic imagery and structural supports in Clement’s book. Panels bleed into the edges of some pages while other pages parody the conventions of baroque tableaux. When El Protector severs the hands of Juan Grande, for instance, the page is presented in the form of one of the stations of the cross, complete with a title that reads ‘santísimo destino doloroso’ (most holy and painful destiny; see Fig. 3.7). The narrative in Operación Bolívar rarely develops through a stable temporal progression performed in the type of panel-to-panel transitions enumerated by Scott McCloud in his analysis of classic comic book narration.46 Rather, through the emphasis on the page as a primary unit, the reader is forced to forge plurivectorial paths across the text. The account of the Operación Bolívar conspiracy, for instance, is told through a series of collages in which the reader is encouraged to make connections between historically disconnected elements such as a portrait of Simón Bolívar and a newspaper cutting concerning free trade agreements in the Americas (see Fig. 3.8). The complicating of panel-to-panel transitions in this way echoes the form of pre-Conquest codices, which were traditionally presented as folding ‘books’, created from long strips of bark, leather or other materials. Zamora draws out the baroque logic of the screenfold format in a way that clearly echoes the mode of plurivectorial narration required of Operación Bolívar’s reader: ‘The screenfold structure allows the interpreter to see several folds at once, to consult folds in clusters rather than consecutively, to flash forward and back and across – that is, to move multidirectionally through the space of astronomical and calendrical signs’.47 The mechanistic Cartesian vision represented by the scientific drawings is unsettled by the way in which the frame repeatedly folds into the image, thereby undermining the reader’s distance from the storyworld. As frame and panel repeatedly fold into one another the reader’s position of detached externality is destabilized. This structural dynamic echoes the manner in which the figure of the baroque angel in the book embodies a fracturing of the dominant scopic regime of modernity.

Fig. 3.7

Baroque tableau in Operación Bolívar (Edgar Clement)

Fig. 3.8

Collage technique in Operación Bolívar (Edgar Clement)

Claire Farago argues that post-Conquest codices echo the reconceptualization of the human carried out in the Council of Valladolid in 1550, in which Bartolomé de las Casas contested Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda’s claim that the indigenous inhabitants of New Spain were less than human and therefore the ‘natural slaves’ of the Spanish by asserting that ‘all the world is human’.48 On the one hand, this functions at a thematic level in the attempts by missionaries to rework their definitions of the human to incorporate the cultures and traditions of the indigenous inhabitants of the newly conquered lands. Parry points out that one of the elements that Tovar excised from Durán’s history was the theory – popular at the beginning of the sixteenth century – that the indigenous inhabitants were descendents of the Lost Tribes of Israel. The reasoning behind this theory was a refusal to accept that God would have left a branch of the human race isolated and ‘cut off from the possibility of salvation’.49 On the other hand, this renegotiation of human limits also takes place at a structural level through the temporary disruption of hierarchies between word and image and through the partial introduction of picture-based language systems into the heart of Renaissance print culture. One aspect of these texts that made them seem dangerous to sixteenth-century Spanish bureaucrats was the fascination they evidenced for the role of images in Mesoamerican cultures. Zamora explains that ‘Indigenous American cultures privileged the capacity of the visual image to be, or become, its object or figure. The image contained its referent, embodied it, made it present physically and experientially to the beholder’.50 This animation of the image is a counterpart to the permeability of boundaries between the body and the world that pervades the pre-Conquest codices and is retained in spectral form in the post-Conquest texts. Operación Bolívar makes a connection between the way codices function as vehicles for the redefinition of what is understood to be human and the use of the graphic novel to perform posthuman subjectivity. The text compares the breaching of the boundaries between the human subject and the non-human object in both the baroque aesthetic and the distribution of cognitive and affective processes beyond the boundaries of the human in digital culture. The decentredness of the graphic novel structure, caught in the tensions between written word and image, stages this distributed conception of life.

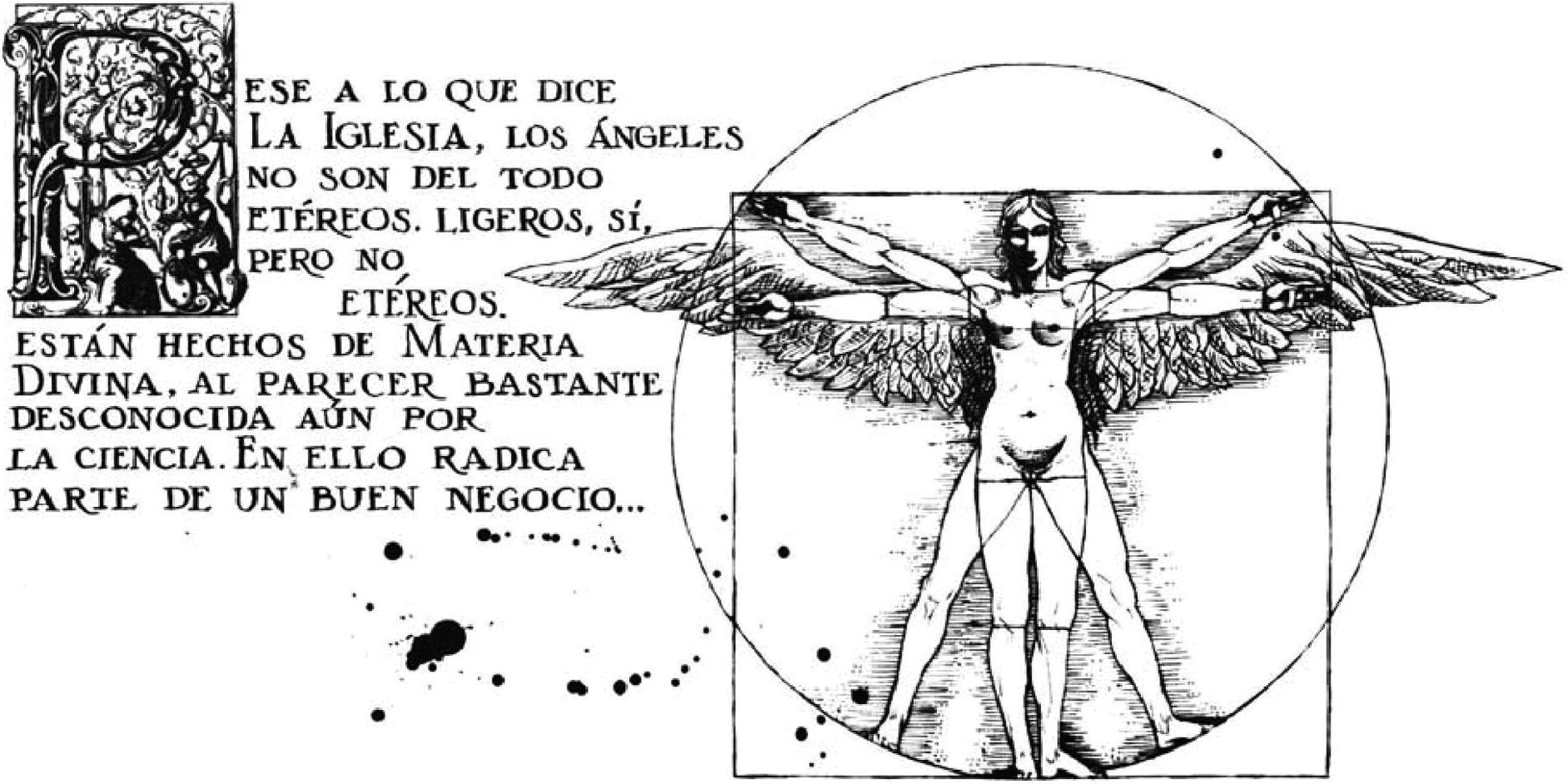

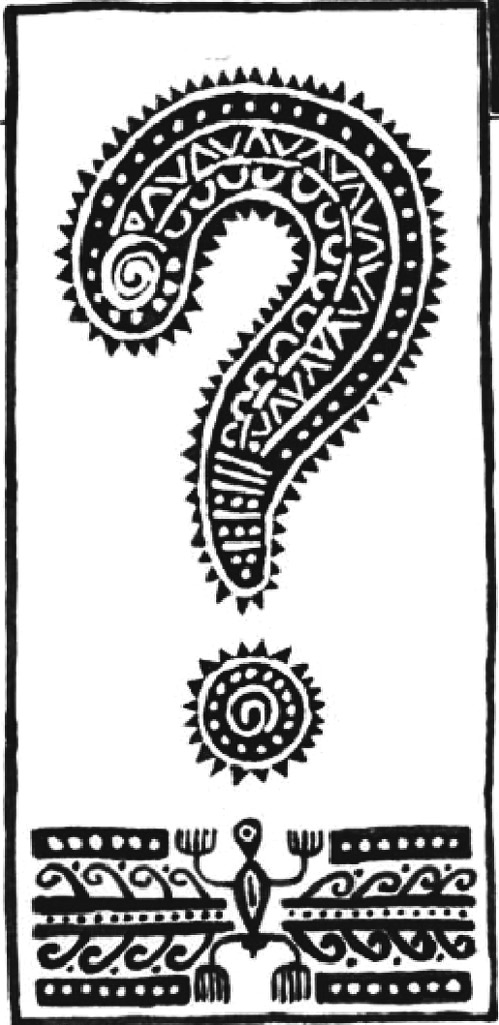

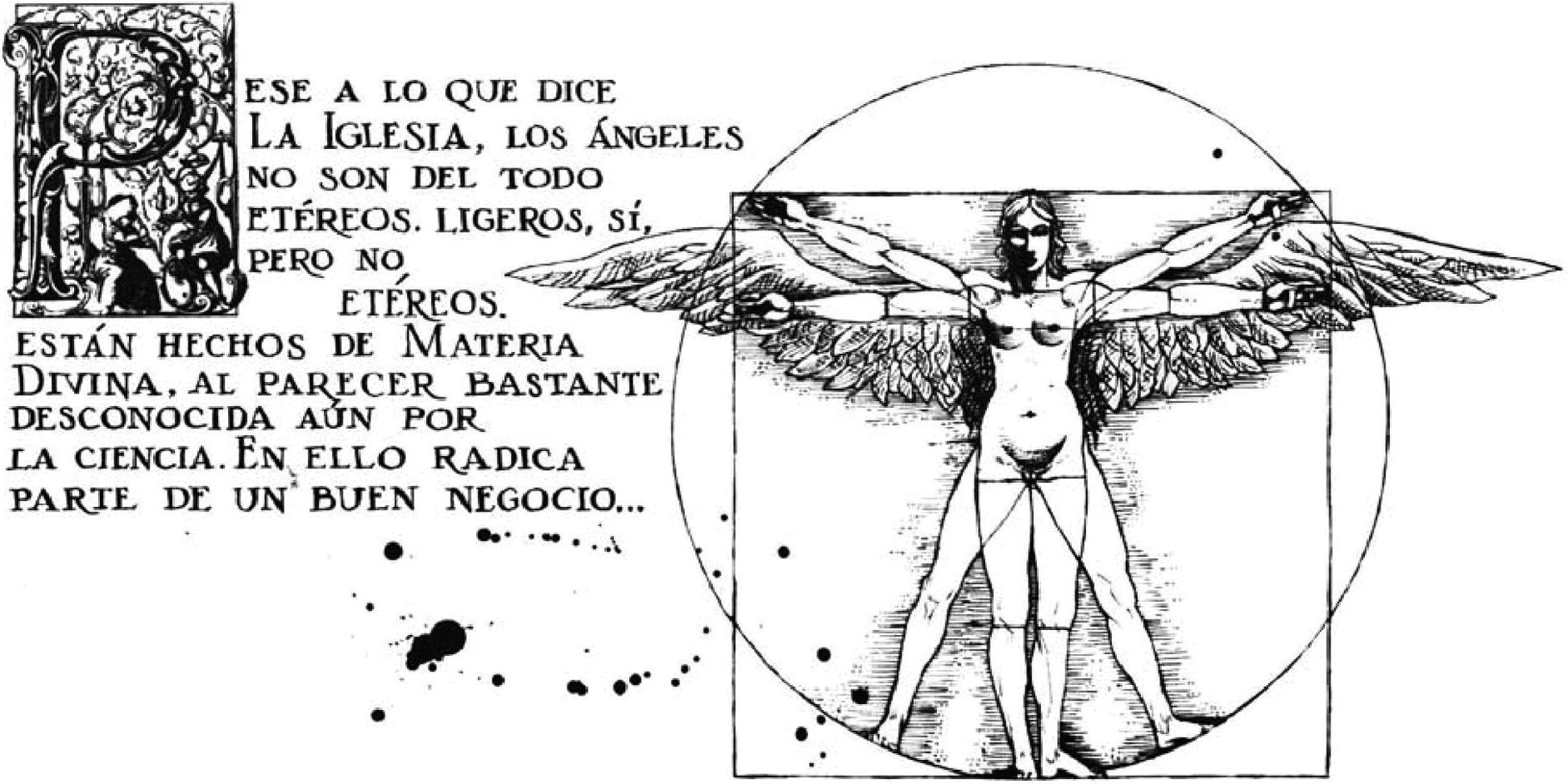

The ongoing intermedial connections that structure the baroque aesthetic of Operación Bolívar have the effect of placing a strong emphasis on the materiality of both the sixteenth-century codices and the graphic novel itself. The frequent use and adaptation of pre-Columbian designs (see Fig. 3.9) and the pervasive uncertainty surrounding the status of frames and borders undermine the suppression of material specificity central to the tradition of textual scholarship that, in Hayles’ argument discussed in the introduction, underpins the dominant discourses of humanism. However, through this emphasis on materiality, Operación Bolívar also problematizes the tendency in posthumanist discourse to caricature Renaissance humanism as being dominated by a commitment to the dematerialized, unified human subject. Clement repeatedly draws the reader’s attention to the textures of the media used in the interests of conquest and domination, from the imitations of Inquisitorial documents in the Intermezzo section of the book to the collage of newspaper cuttings celebrating free trade agreements in the 1990s. This emphasis on their materiality echoes Mignolo’s argument that the written word occupied a privileged position in the Renaissance systems of knowledge that animated the Conquest. In her call for a focus on materiality in Latin American media theory, Shirin Shenassa points out that the Spanish humanist and grammarian Antonio de Nebrija in his Gramática castellana of 1492 argued that a strictly regulated and codified Castilian Spanish was a ‘necessary precondition for national coherence as well as for the expected expansion of the Spanish Empire’.51 It was only the advent of print media – which was contemporaneous with the Conquest – that made this regulation possible. In this way, Clement’s book pre-empts a number of recent warnings that critical posthumanism should be alert to the complexities and contradictions of the humanist discourses it critiques. Joseph Campana and Scott Maisano argue that the Renaissance humanism rejected by much contemporary work on posthumanist thought is a straw man that bears little resemblance to discourses elaborated from the fourteenth to the seventeenth century that presented the human as ‘at once embedded and embodied in, evolving with, and decentred amid a weird tangle of animals, environments, and vital materiality’.52 Instead, as a counterpart to Latour’s assertion that ‘we have never been modern’, they suggest that ‘we have always been posthuman’.53Operación Bolívar repeatedly emphasizes the paradoxically posthumanist status of certain strands of Renaissance thought through its enactment of the ‘becoming-minor’ of the historical baroque aesthetic. By pointing to the differential logic shared by the historical baroque and the information aesthetic of the digital age through the figure of the angel, the book reveals a posthumanist logic at the heart of one of the main aesthetic vehicles for humanism during the colonial period. The blurring of neat distinctions between humanism and posthumanism carried out by Clement is emphasized in satirical fashion by the appearance of an image of an angelic version of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man alongside the butcher’s diagram of angel cuts (see Fig. 3.10).

Fig. 3.9

Adaptation of pre-Columbian design in Operación Bolívar (Edgar Clement)

Fig. 3.10

Angelic version of Vitruvian Man in Operación Bolívar (Edgar Clement)