Angelology

The baroque construction of angels in Operación Bolívar plays a key role in the process of media (an)archaeology carried out by the book. Clement uses the figure of the angel as a tool for intervening into the increasingly dynamic interplay between materiality and abstraction in digital culture. Many of the critical analyses of Clement’s work published to date centre on his depiction of angels. Héctor D. Fernández L’Hoeste argues that the use of angelic figures in Operación Bolívar demonstrates the extent to which the book remains caught within a national imaginary. Despite Clement’s satirical tone, his work ‘encaja bien dentro de las matrices historiográficas del acontecer nacional’ (fits neatly into the official historiographical mould of national events).22 In particular, the figure of the angel in Operación Bolívar reproduces the interconnections between Church and State produced by ‘nuestra tradición estética y el relato national’ (our aesthetic tradition and the national narrative).23 As proof of this, L’Hoeste cites the depiction of a bare-breasted angel in the first part of the book, which he compares to the Ángel de Independencia statue, the national icon built in 1910 to commemorate a century since national independence. The misogynistic detailing of her body, together with the fact that no sooner does she appear in the book than she is brutally dismembered by the two cazadores Leonel and Román, underscore L’Hoeste’s thesis that Clement’s angelic depictions reinforce dominant patriarchal discourses about nationhood.24

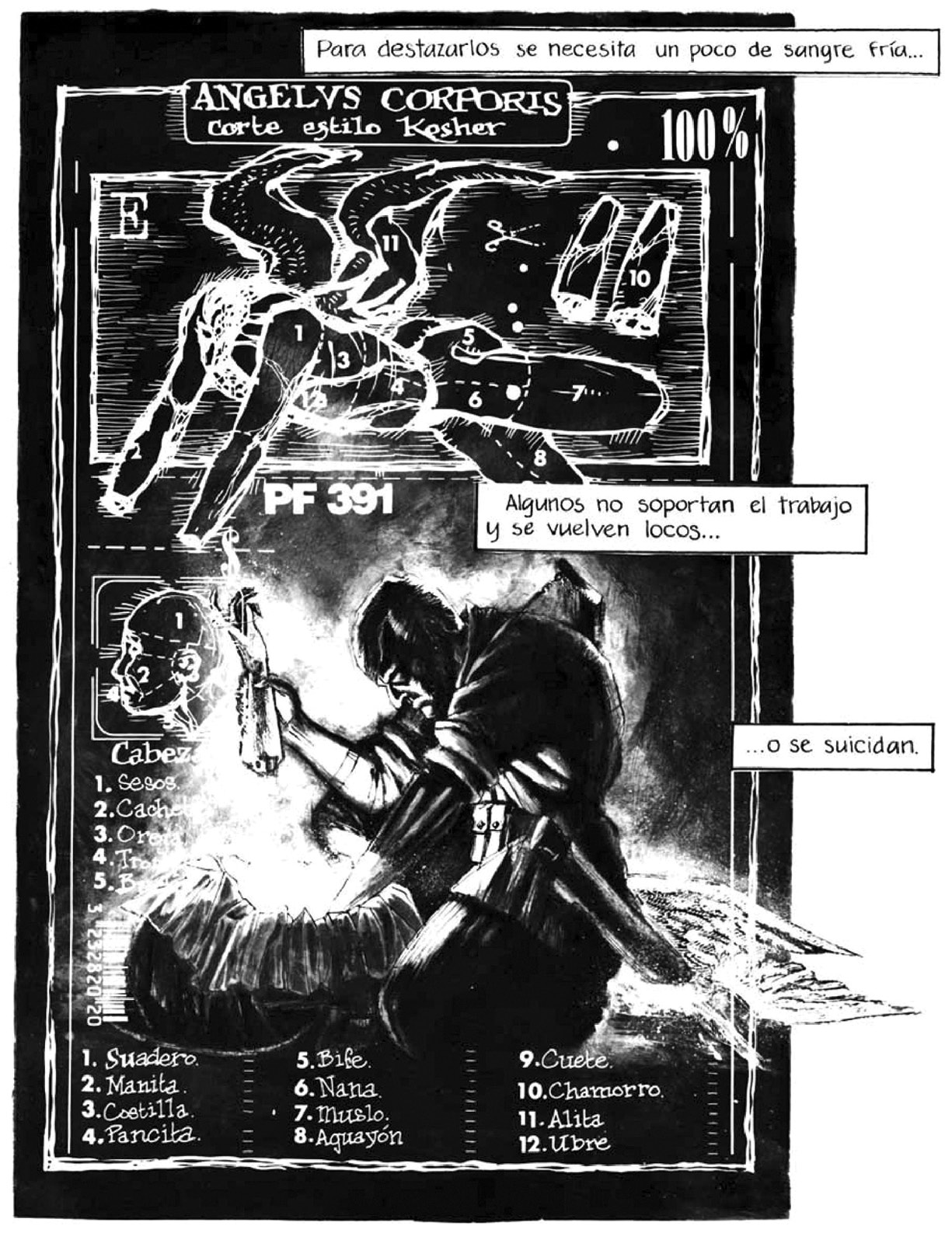

However, Operación Bolívar taps into a more complex and transnational tradition of angelic representations than Fernández L’Hoeste suggests, and specifically one that uses the figure of the angel to probe the nature of postmodern media culture. In this way, the angel becomes central to Clement’s baroque exploration of the complex interactions between materiality and abstraction in digital culture. Brian McHale uses the term ‘postmodern angelology’ to refer to the use in the postmodern North American fiction of Thomas Pynchon and William T. Vollmann of the figure of the angel ‘as a realized metaphor of the violation of ontological boundaries’.25 The angel shares its condition of liminality and its status as a conduit between adjoining ontological worlds with the cyborg. Both the angel and the cyborg ‘symbolise the human aspiration to achieve a state beyond the human’.26 In recognition of the fact that, in McHale’s words, the ‘angel-function’ has been largely ‘science-fictionalised’, cyberpunk novels such as Schismatrix (1985) by Bruce Sterling and Wetware (1988) by Rudy Rucker have used angelic imagery in their fictional constructions of cyborgs. One of the main sources of humour in Operación Bolívar is the trope of the ‘hollow’ postmodern angel: the angel ‘emptied of its otherworldliness and brought ingloriously down to earth’.27 The epilogue section at the end of the book contains a ‘dramatis personae’ that doubles up as a typology of the angels and cazadores that populate Angelópolis. The entry for El Protector, the fallen angel who helps the CIA to effect their plan, tells us that he became a mercenary ‘quando se privatizó El Cielo’ (when Heaven was privatized; see Fig. 3.2). The fate of the angels also parodies the complex interconnections that characterize late-capitalist financial structures. Subsequent to being hired by the CIA, El Protector is trained to destroy the Vatican with weapons that were manufactured by a corporation in which the Catholic Church itself is an important shareholder.28